Since the advent of South Africa’s democratic dispensation, discourse on gender, and particularly the role of women in society, has gained prominence. Enshrined in the Constitution are certain inalienable rights that guarantee girls and women equality under the law. The African National Congress, the governing party since 1994, has gone so far as to mandate that women comprise 50% of their leadership; and indeed, South Africa has one of the highest rates of female representation in its parliament globally. Yet, paradoxically, South Africa also has one of the highest incidences of reported rape anywhere in the world. Further, women in our country, as is the trend globally, are disproportionally poor and carry the greatest disease burden.

Confronted with this contradiction, there are moments on the national calendar in which South Africa pauses to consider the role of women in society: to celebrate their contributions and to examine their challenges. As South Africa concluded the 16 days of activism against the abuse of women and children and celebrated the 66th birthday of Steve Biko last month, we at the Steve Biko Foundation take a moment to consider Black Consciousness and Gender.

In this, the fifth edition of the FrankTalk Journal, we reflect on the ways in which the ideology of Black Consciousness (BC) historically contributed to the liberation of women, and the ways in which this philosophy continues to shape feminist thinking in the 21st century. With that said, we also explore the short-comings of BC and the Black Consciousness Movement in advancing gender equality. Our hope is that this issue of the FrankTalk journal will provide another framework through which to understand these topics—and make real notions of equality.

To lead us into this discussion, we are pleased to bring you contributions from four individuals who have reflected on Black Consciousness and Gender in their various capacities as feminist scholars, political analysts and activists.

We look forward to bringing you more perspectives on contemporary socio-economic and political issues in the coming editions of the journal and invite you to share your contributions with us via email: dibuseng@sbf.org.za or the FrankTalk Blog

www.sbffranktalk.blogspot.com. Continue the dialogue through Facebook

www.facebook.com/TheSteveBikoFoundation and Twitter

www.twitter.com/BikoFoundation .

To access the FrankTalk Journal, please visit http://www.sbf.org.za/Main_Site/frank-talk-journal .

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Dom Coyote to Give Workshops at The Steve Biko Centre

The Steve Biko Centre,

in partnership with

the British Council Residency Programme;

Presents

Dom Coyote

The London-based artist, Dom Coyote, will give workshops and compose music with The Steve Biko Centre's Abelusi and four students from the University of Fort Hare.

Date: 04 until 23 February 2013

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, Eastern Cape

Dom Coyote is a musician, performer and writer of stories and songs. He is an associate artist with Kneehigh Theatre and studied Performance writing at Dartington College of Arts as well as performing and composing for companies such as Kneehigh, The Royal Shakespeare Company, Art Angel, West Yorkshire Play House and Battersea Arts Centre. Dom is also a lead artist on two major projects - Folk in a Box, a One on One musical experience, currently being exhibited at the Venice Biennale 2012, and The Raun Tree, an apocalyptic fairytale told through ten songs, on tour throughout 2012. In 2009 Dom was awarded the BAC Jim Marcovitch Bursary for music and theatre, allowing him to develop his work as a lead artist. In February 2013, Dom will continue this development through an invitation and funding from The British Council to travel around South Africa and learn about indigenous music and song. There will be three performances at the end of the workshop.

For more information please contact Mr. Jongi Hoza on 043 605 6726.

The Business Incubator: Tendering Workshop

The Business Incubator, an initiative of the Steve Biko Centre, invites you to a Tendering Workshop in Ginsberg.

Facilitator: Lungile Sululu from the Steve Biko Foundation

Date: February 4, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, Eastern Cape

Cost: R20

For more information please contact Mr. Sululu on 043 605 6700 or email lungiles@sbf.org.za

Facilitator: Lungile Sululu from the Steve Biko Foundation

Date: February 4, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, Eastern Cape

Cost: R20

For more information please contact Mr. Sululu on 043 605 6700 or email lungiles@sbf.org.za

The Business Incubator Workshop: FNB Business Banking

The Business Incubator, an initiative of the Steve Biko Centre, invites you to a workshop on FNB Business Banking to be held in Ginsberg.

Facilitator: Representative from FNB

Date: February 1, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, King William's Town, Eastern Cape

Cost: Free

NB: Clients are urged to book in advance for the Micro MBA Workshop.

Facilitator: Representative from FNB

Date: February 1, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, King William's Town, Eastern Cape

Cost: Free

NB: Clients are urged to book in advance for the Micro MBA Workshop.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Biography of the Week: Sol Plaatje

Names: Plaatje, Solomon Tshekisho

Born: 9 October 1876, Boshof district, Orange Free State

Died: 19 June 1932, Johannesburg, South Africa

In summary: Teacher, court interpreter and clerk to the Mafeking administrator of Native Affairs, author, journalist, linguist, and first Secretary-General of the SANNC, member of the SANNC deputation that travelled to London to appeal to the British Government against the 1913 Land Act

Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje was born on 9 October 1876 in the Boshof district of the Orange Free State. His parents were Christians who belonged to the Setswana-speaking Barolong tribe. About the time he was born, his parents moved to the Pniel mission station of the Lutheran Berlin Mission Society, near Barkly West, and it was there that Plaatje received his only formal education, a few years in the elementary grades. He remained at Pniel for several years as an assistant teacher, studying further with the aid of the missionaries. In 1894 he went to Kimberley, where he found work as a postman, continued his private studies, and eventually distinguished himself on the civil service examinations. On the eve of the Boer War he was sent to Mafeking as an interpreter, and during the siege of Mafeking in 1899 - 1900 he acted as both court interpreter and clerk to the Mafeking administrator of Native affairs. He was proficient in at least eight languages, including German and Dutch, as well as English and all the major African vernaculars.

Advancement in the civil service being closed to him, Plaatje turned to journalism at the end of the war, and, with financial backing from Silas Molema, chief of the Barolong, he established the first Setswana-English weekly, Koranta ea Becoana (Newspaper of the Tswana) in 1901. This existed, under Plaatje's editorship, for six or seven years, after which he moved from Mafeking to Kimberley. There he established a new paper; Tsala ea Becoana, later renamed Tsala ea Batho (The Friend of the People). While producing these papers, Plaatje also contributed many articles to other papers, particularly to the Kimberley Diamond Fields Advertiser. When the South African Native National Congress (later called the African National Congress) was formed in 1912, Plaatje was chosen its first secretary-general. An articulate opponent of tribalism, he exemplified the new spirit of national unity among African intellectuals. (At a time when intertribal marriages were still uncommon, Plaatje had married a Fingo. His wife Elizabeth was a sister of H. I. Bud-Mbelle.)

The first major campaign of the SANNC was against the Land Act of 1913, a measure that drastically curtailed the right of Africans to own or occupy land throughout the Union. In 1914 Plaatje went to Britain as a member of the deputation charged with appealing to the British government against the Act. The mission proved futile, but Plaatje decided to stay behind after the departure of the rest of the deputation, and he remained in Britain until February 1917, when he returned to South Africa. During this time he lectured, worked as a language assistant at London University, and produced three books, including a detailed and moving appeal against the Land Act, Native Life in South Africa, Before and Since the European War and the Boer Rebellion (1916). The other two works, Sechuana-Proverbs, With Literal Translations and Their English Equiv¬alents and A Sechuana Reader, written with Daniel Jones of London University, also appeared in 1916.

He is said to have attended the first pan-African conference in Paris in February 1919 and also the 1921 conference, but no evidence supports this. He did return to London in May 1919, a few months after the SANNC deputation to Versailles had left South Africa. Late in 1919 he took part in a meeting with British Prime Minister Lloyd George. In December 1920 he went to Canada and the United States, where he traveled widely. Meeting with leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, he arranged for an American edition of his book. Native Life, to appear.

At the end of 1923 he returned to South Africa. He continued to write, and when Parliament was in session he traveled to Cape Town to cover the sessions and to lobby for African interests as a representative of the ANC. Influenced by his experiences in the United States, he became involved in the Joint Council movement. He also joined the African People's Organization of Abdul Abdurahman. He made a trip to the Congo to observe conditions there and was active in civic affairs in Kimberley. Although his relations with the ANC were sometimes uneasy, in December 1930 he accompanied an ANC deputation to the Native affairs department to register African complaints against the pass laws. He died of pneumonia while on a trip to Johannesburg on 19 June 1932.

In addition to the works already mentioned, his writings include a novel, Mhudi, An Epic of South African Native Life a Hundred Years Ago (1930), The Mote and the Beam: An Epic on Sex-Relationship 'Twixt White and Black in British South Africa (1921), and translations of four Shakespeare plays into Setswana.

In 1972 his Mafeking diary, discovered in 1969 and edited by John L. Comaroff, was published under the titleThe Boer War Diary of Sol T. Plaatje: An African at Mafeking.

Biography retrieved from South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/solomon-tshekisho-plaatje

Born: 9 October 1876, Boshof district, Orange Free State

Died: 19 June 1932, Johannesburg, South Africa

In summary: Teacher, court interpreter and clerk to the Mafeking administrator of Native Affairs, author, journalist, linguist, and first Secretary-General of the SANNC, member of the SANNC deputation that travelled to London to appeal to the British Government against the 1913 Land Act

Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje was born on 9 October 1876 in the Boshof district of the Orange Free State. His parents were Christians who belonged to the Setswana-speaking Barolong tribe. About the time he was born, his parents moved to the Pniel mission station of the Lutheran Berlin Mission Society, near Barkly West, and it was there that Plaatje received his only formal education, a few years in the elementary grades. He remained at Pniel for several years as an assistant teacher, studying further with the aid of the missionaries. In 1894 he went to Kimberley, where he found work as a postman, continued his private studies, and eventually distinguished himself on the civil service examinations. On the eve of the Boer War he was sent to Mafeking as an interpreter, and during the siege of Mafeking in 1899 - 1900 he acted as both court interpreter and clerk to the Mafeking administrator of Native affairs. He was proficient in at least eight languages, including German and Dutch, as well as English and all the major African vernaculars.

Advancement in the civil service being closed to him, Plaatje turned to journalism at the end of the war, and, with financial backing from Silas Molema, chief of the Barolong, he established the first Setswana-English weekly, Koranta ea Becoana (Newspaper of the Tswana) in 1901. This existed, under Plaatje's editorship, for six or seven years, after which he moved from Mafeking to Kimberley. There he established a new paper; Tsala ea Becoana, later renamed Tsala ea Batho (The Friend of the People). While producing these papers, Plaatje also contributed many articles to other papers, particularly to the Kimberley Diamond Fields Advertiser. When the South African Native National Congress (later called the African National Congress) was formed in 1912, Plaatje was chosen its first secretary-general. An articulate opponent of tribalism, he exemplified the new spirit of national unity among African intellectuals. (At a time when intertribal marriages were still uncommon, Plaatje had married a Fingo. His wife Elizabeth was a sister of H. I. Bud-Mbelle.)

The first major campaign of the SANNC was against the Land Act of 1913, a measure that drastically curtailed the right of Africans to own or occupy land throughout the Union. In 1914 Plaatje went to Britain as a member of the deputation charged with appealing to the British government against the Act. The mission proved futile, but Plaatje decided to stay behind after the departure of the rest of the deputation, and he remained in Britain until February 1917, when he returned to South Africa. During this time he lectured, worked as a language assistant at London University, and produced three books, including a detailed and moving appeal against the Land Act, Native Life in South Africa, Before and Since the European War and the Boer Rebellion (1916). The other two works, Sechuana-Proverbs, With Literal Translations and Their English Equiv¬alents and A Sechuana Reader, written with Daniel Jones of London University, also appeared in 1916.

He is said to have attended the first pan-African conference in Paris in February 1919 and also the 1921 conference, but no evidence supports this. He did return to London in May 1919, a few months after the SANNC deputation to Versailles had left South Africa. Late in 1919 he took part in a meeting with British Prime Minister Lloyd George. In December 1920 he went to Canada and the United States, where he traveled widely. Meeting with leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, he arranged for an American edition of his book. Native Life, to appear.

At the end of 1923 he returned to South Africa. He continued to write, and when Parliament was in session he traveled to Cape Town to cover the sessions and to lobby for African interests as a representative of the ANC. Influenced by his experiences in the United States, he became involved in the Joint Council movement. He also joined the African People's Organization of Abdul Abdurahman. He made a trip to the Congo to observe conditions there and was active in civic affairs in Kimberley. Although his relations with the ANC were sometimes uneasy, in December 1930 he accompanied an ANC deputation to the Native affairs department to register African complaints against the pass laws. He died of pneumonia while on a trip to Johannesburg on 19 June 1932.

In addition to the works already mentioned, his writings include a novel, Mhudi, An Epic of South African Native Life a Hundred Years Ago (1930), The Mote and the Beam: An Epic on Sex-Relationship 'Twixt White and Black in British South Africa (1921), and translations of four Shakespeare plays into Setswana.

In 1972 his Mafeking diary, discovered in 1969 and edited by John L. Comaroff, was published under the titleThe Boer War Diary of Sol T. Plaatje: An African at Mafeking.

Biography retrieved from South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/solomon-tshekisho-plaatje

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Biko on Institutionalised Racism

The racism we meet is not only on an individual basis; it is also institutionalised to make it look like the South African way of life. Although of late there is a feeble attempt to gloss over the overt racist elements in the system, it is still true that the system derives its nourishment from the existence of anti-Black attitudes in the society. To make the lie live even longer, Blacks have to be denied any chance of accidentally proving their equality to the White man.

It is for this reason that there is job reservation, lack of training in skilled work, and a tight orbit around professional possibilities for Blacks. Stupidly enough, the system turns back to say that Blacks are inferior because they have no economists, no engineers, etc. even in spite of the fact that they make it impossible for Blacks to acquire these skills.

Excerpt from S. Biko. "Black Consciousness and The Quest For True Humanity" in I Write What I Like, Picador Africa: Johannesburg

It is for this reason that there is job reservation, lack of training in skilled work, and a tight orbit around professional possibilities for Blacks. Stupidly enough, the system turns back to say that Blacks are inferior because they have no economists, no engineers, etc. even in spite of the fact that they make it impossible for Blacks to acquire these skills.

Excerpt from S. Biko. "Black Consciousness and The Quest For True Humanity" in I Write What I Like, Picador Africa: Johannesburg

Friday, January 25, 2013

Biko… on Self-Perception

I am against the superior-inferior white-black stratification that makes the white a perpetual teacher and the black a perpetual pupil (and a poor one at that). I am against the intellectual arrogance of white people that makes them believe that white leadership is a sine qua non in this country and that whites are divinely appointed pace-setters in progress. I am against the fact that a settler minority should impose an entire system of values on an indigenous people…

I am not working. I am persecuted for my political beliefs or mental beliefs. I have not done anything which is against the law, and I have got no profession as such. So if a guy in a round table is asking, what is your profession? I always say, freedom fighter, precisely because this is what the ‘state’ wants me to do, to sit at home and think about my freedom rather than be involved in creative work…

To understand me correctly, you would have to say that there were no fears expressed.

Excerpts from S. Biko. No Fears Expressed.Edited by M. W. Arnold. Mutloatse Heritage Trust. 2007.

I am not working. I am persecuted for my political beliefs or mental beliefs. I have not done anything which is against the law, and I have got no profession as such. So if a guy in a round table is asking, what is your profession? I always say, freedom fighter, precisely because this is what the ‘state’ wants me to do, to sit at home and think about my freedom rather than be involved in creative work…

To understand me correctly, you would have to say that there were no fears expressed.

Excerpts from S. Biko. No Fears Expressed.Edited by M. W. Arnold. Mutloatse Heritage Trust. 2007.

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Call for Articles: The Contemporary Relevance of Robert Sobukwe

Opportunity Closing Date: February 15, 2013

Opportunity Type: Call for Articles/Papers

The Steve Biko Foundation is calling for reflections on the legacy of South Africa’s freedom fighter, Robert Sobukwe. The topic is The Contemporary Relevance of Robert Sobukwe. Submissions may focus on any field that was impacted by Sobukwe; but of particular interest are:

Heritage

Land

Pan Africanism

Language

Culture

Education

Identity

Civil Disobedience

Submissions will be published in the March 2013 issue of the Steve Biko Foundation’s FrankTalk Journal, as well as on the FrankTalk Blog.

The length of the submission should be between 1000 and 2500 words in MS Word.

Papers/articles should be submitted to Dibuseng Kolisang at dibuseng@sbf.org.za. Alternatively, papers may be faxed to +27.11.403.8835.

For more information email Dibuseng or call on +27.11.403.0310.

Opportunity Type: Call for Articles/Papers

The Steve Biko Foundation is calling for reflections on the legacy of South Africa’s freedom fighter, Robert Sobukwe. The topic is The Contemporary Relevance of Robert Sobukwe. Submissions may focus on any field that was impacted by Sobukwe; but of particular interest are:

Heritage

Land

Pan Africanism

Language

Culture

Education

Identity

Civil Disobedience

Submissions will be published in the March 2013 issue of the Steve Biko Foundation’s FrankTalk Journal, as well as on the FrankTalk Blog.

The length of the submission should be between 1000 and 2500 words in MS Word.

Papers/articles should be submitted to Dibuseng Kolisang at dibuseng@sbf.org.za. Alternatively, papers may be faxed to +27.11.403.8835.

For more information email Dibuseng or call on +27.11.403.0310.

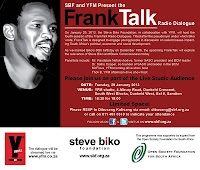

FrankTalk Radio Dialogue: Biko and Black Consciousness, Today

SBF and YFM Present: The FrankTalk Radio Dialogue

On January 29, 2013, the Steve Biko Foundation, in collaboration with YFM, will host the fourth session of the FrankTalk Radio Dialogues. Titled after the pseudonym under which Biko wrote, FrankTalk is designed to engage young people in discussion on salient issues impacting South Africa’s political, economic and social development.

As we marked Biko’s 66th birthday on December 18th, the upcoming FrankTalk will explore the relevance of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness Today.

Panellists include: Mr. Pandelani Nefolovhodwe, former SASO president and BCM leader

Dr. Saths Cooper, co-founder of SASO and BCM leader

MoFlava, YFM morning drive show host

Tholi B, YFM afternoon drive show host

Please join us as part of the Live Studio Audience.

DATE: Tuesday, 29 January 2013

VENUE: YFM studio, 4 Albury Road, Dunkeld Crescent,

South West Blocks, Dunkeld West, Ext 8, Sandton

TIME: 18:30 for 19:00

Limited Space!

Please RSVP to Dibuseng Kolisang via email: dibuseng@sbf.org.za or call on 011 403 0310 to indicate your attendance

On January 29, 2013, the Steve Biko Foundation, in collaboration with YFM, will host the fourth session of the FrankTalk Radio Dialogues. Titled after the pseudonym under which Biko wrote, FrankTalk is designed to engage young people in discussion on salient issues impacting South Africa’s political, economic and social development.

As we marked Biko’s 66th birthday on December 18th, the upcoming FrankTalk will explore the relevance of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness Today.

Panellists include: Mr. Pandelani Nefolovhodwe, former SASO president and BCM leader

Dr. Saths Cooper, co-founder of SASO and BCM leader

MoFlava, YFM morning drive show host

Tholi B, YFM afternoon drive show host

Please join us as part of the Live Studio Audience.

DATE: Tuesday, 29 January 2013

VENUE: YFM studio, 4 Albury Road, Dunkeld Crescent,

South West Blocks, Dunkeld West, Ext 8, Sandton

TIME: 18:30 for 19:00

Limited Space!

Please RSVP to Dibuseng Kolisang via email: dibuseng@sbf.org.za or call on 011 403 0310 to indicate your attendance

Sobukwe, Politics and the Sharpeville Massacre

In 1948 Sobukwe and three of his friends launched a daily publication called Beware. Topics appearing in the paper included non-collaboration and critiques of Native Representative Councils and Native Advisory Boards. That same year Sobukwe joined the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL), which was established on the university campus by Godfrey Pitje, a lecturer in the Department of African Studies who later became the league’s president. Sobukwe and his classmates were at first sceptical of the ANCYL because they felt that the African National Congress (ANC) had been compromised by its continuing participation in the Native Representative Council and the township Advisory Boards.

A year later, in 1949, Sobukwe was elected president of the Fort Hare Students' Representative Council (SRC), where he proved himself to be an effective orator. His speech as outgoing president of the SRC in October 1949 established him as an important figure among his peers. In December he was selected by Pitje to become the National Secretary of the ANCYL. During this period he became influenced by the writings of Anton Lembede and he began adopting an Africanist position within the ranks of the ANC. During 1949 Sobukwe met Veronica Mathe at Alice Hospital, where she was a nurse in training. The couple got married in 1950.

In 1950, Sobukwe was appointed as a teacher at Jandrell Secondary School in Standerton, where he taught History, English and Geography. In 1952 he lost his teaching position after speaking out in favour of the Defiance Campaign. His dismissal, however, did not last long and he was soon reinstated. Although Sobukwe was secretary of the ANC’s Standerton branch from 1950 to 1954, he was not directly involved in mainstream ANC activities.

In 1954 Sobukwe moved to Johannesburg, where he became a lecturer in African Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand – a job which earned him the nickname ‘the Prof’. He settled in Mofolo, Soweto, where he joined a branch of the ANC. Sobukwe became editor of The Africanist in 1957 and soon began to criticise the ANC for allowing itself to be dominated by what he termed 'liberal-left-multi-racialists'. In 1958 Sobukwe completed his Honours dissertation at Wits entitled “A collection of Xhosa Riddles”.

Politically, Sobukwe was strongly Africanist, believing that the future of South Africa should be in the hands of Black South Africans. As a result of his septicism towards the multi-racial path the ANC was following, Sobukwe was instrumental in initiating an Africant breakaway from the ANC in 1958, which led to the birth of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). He stated:

“In 1955 the Kilptown Charter was adopted, which according to us, is irreconcilable conflict with the 1949 Programme seeing that it claims land no longer Africa, but is auctioned for sale to all who live in this country. We have come to the parting of the ways and we are here and now giving notice that we are disassociating ourselves from the ANC as it is constituted at present in the Transvaal.”

At the PAC’s inaugural congress, held in Orlando from 4 to 6 April 1959, Sobukwe was unanimously elected the party’s first President. Sobukwe's eloquence as a public speaker, his intelligence and commitment to his cause soon established him as natural leader, and helped him rally support for the PAC. Sobukwe’s opposition to ‘multi-racialism’ in favour of ‘non-racialism’ is apparent in an extract from his inaugural speech at the PAC launch in 1959.

A week after the ANC announced its anti-pass campaign in December 1959, the PAC announced that it was planning to initiate a campaign against the pass laws with the aim to free South Africa by 1963. On 16 March 1960, Sobukwe wrote to the Commissioner of Police, Major General Rademeyer, stating that the PAC would be holding a five-day, non-violent, disciplined, and sustained protest campaign against pass laws, starting on 21 March. On 21 March 1960, at the launch of the PAC’s anti-pass campaign, Sobukwe resigned from his post as lecturer at the University of Witwatersrand. He made last-minute arrangements for the safety of his family and left his home in Molofo. He intended to give himself up for arrest at the Orlando Police Station in the hope that his actions would inspire other Black South Africans. Along the eight kilometre walk to the police station, small groups of men joined him from neighbouring areas like Phefeni, Dube and Orlando West. As the small crowd approached the station, most of the marchers, including Sobukwe, were arrested and charged with sedition. When an estimated group of 5000 marchers reached Sharpeville police station, the police opened fire killing 69 people and injuring 180 others in what became known as the Sharpeville Massacre.

An order was issued on 25 March 1960 for the banishment of Sobukwe to the Driefontein Native Trust Farm, Vryburg District, [Northern Cape, now North West Province]. At the time, Sobukwe was living in Mafolo Bantu Township, Johannesburg, Transvaal [now Gauteng].

The documentation on the banishment noted that Sobukwe and Leballo had both been arrested and were awaiting trial “but it [was] necessary to have a banishment order in hand just in case they are released.” Sobukwe never spent time in banishment as he was sentenced to imprisonment for incitement.

On 4 May 1960 Sobukwe was sentenced to three years in prison for inciting Africans to demand the repeal of the pass laws. He refused to appeal against the sentence, as well as the aid of an attorney, on the grounds that the court had no jurisdiction over him as it could not be considered either a court of law or a court of justice. At the end of his three-year sentence on 3 May 1963, Parliament enacted a General Law Amendment Act. The Act included what was termed the 'Sobukwe Clause', which empowered the Minister of Justice to prolong the detention of any political prisoner indefinitely. Subsequently, Sobukwe was moved to Robben Island, where he remained for an additional six years. The Clause was never used to detain anyone else. The Sobukwe Clause was renewed every year – when it was due to expire on 30 June 1965, the government renewed it.

While on Robben Island, Sobukwe was kept in solitary confinement – his living quarters were separate from the main prison and he had no contact with any other prisoners. He was, however, allowed access to books and civilian clothes. As a result, Sobukwe spent much of his time studying, and he obtained a degree in Economics from the University of London. In 1964 Sobukwe was offered a job by the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and the Montgomery Fellowship for Foreign Aid in the US. He applied to leave the country with his family to take up the employment but was denied permission by the Minister of Justice, John Vorster.

Sobukwe was released from prison in May 1969 and was banished to Galeshewe in Kimberley, where he was joined by his family. However, he remained under twelve-hour house arrest and his banning order prohibited him from participating in any political activity. In 1970 Sobukwe successfully applied for a teaching post at the University of Wisconsin in the US, but the Apartheid government refused his request for a passport despite assurances that he would be given a visa by the US government. When he applied to leave South Africa permanently together with his family in 1971, the South African government again refused to give him permission.

While the restrictions kept him under house arrest and denied him permission to leaving South Africa, he was permitted to attend family gatherings outside Kimberley. For instance, in July 1973 Sobukwe was granted permission to leave Kimberley to visit his son Dalindyebo, who had been hospitalised in Johannesburg. In June 1974 Sobukwe spent three days in Johannesburg visiting his wife, who underwent an operation at a hospital in Johannesburg. Finally, in 1975, Sobukwe’s mother died and he applied to the Chief Magistrate of Kimberley for a permit to leave the town in order to attend the funeral. He was granted permission on condition that he report to the police station upon arrival and departure, and that he return to Kimberley by midnight on Friday 9 May 1975, a day after the funeral.

Sobukwe began studying Law while he was under house arrest. He completed his articles in Kimberley, and established his own law firm in 1975. The government’s Department of Justice initially denied him permission to enter the courts, but reversed the decision and withdrew the prohibition after the government relaxed a clause that banned Sobukwe from entering a court of law except as an accused or as a witness. However, newspapers were not allowed to quote him when he argued in court.

Shortly after opening his law practice, Sobukwe fell ill. In July 1977 he applied for permission to go for medical treatment in Johannesburg. Benjamin Pogrund, a close family friend, intervened and on 9 September Sobukwe was allowed to leave Kimberley for Johannesburg under strict conditions. He was diagnosed with lung cancer and his condition was deemed serious. Consequently, Sobukwe was transferred to Groote Schuur hospital in Cape Town. While he was in the hospital the security branch instructed the medical staff not to permit any visitors to visit him except his family.

Sobukwe’s wife applied for permission from the Cape magistrate for him to stay with a family friend, Bishop Pat Matolengwe. After deliberate delays by the government, on 14 October he was temporality discharged and Bishop Matolengwe took him from the hospital. Sobukwe was sent back to Kimberley, from he was due to travel back to Cape Town for another round of treatment. Each time he left Kimberley, he had to report to the police station – which he also had to do when he arrived at or left Cape Town.

The government deliberately made it harder for Sobukwe to receive treatment by insisting that he should comply with the conditions of his restrictions, despite his evidently failing health. On 27 February 1978 Sobukwe died from lung complications at Kimberley General Hospital. His funeral was held on 11 March 1978 and he was buried in Graaff-Reinet. Today, he remains a celebrated political figure in the struggle for a democratic South Africa.

Biography Retrieved from South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/robert-mangaliso-sobukwe

A year later, in 1949, Sobukwe was elected president of the Fort Hare Students' Representative Council (SRC), where he proved himself to be an effective orator. His speech as outgoing president of the SRC in October 1949 established him as an important figure among his peers. In December he was selected by Pitje to become the National Secretary of the ANCYL. During this period he became influenced by the writings of Anton Lembede and he began adopting an Africanist position within the ranks of the ANC. During 1949 Sobukwe met Veronica Mathe at Alice Hospital, where she was a nurse in training. The couple got married in 1950.

In 1950, Sobukwe was appointed as a teacher at Jandrell Secondary School in Standerton, where he taught History, English and Geography. In 1952 he lost his teaching position after speaking out in favour of the Defiance Campaign. His dismissal, however, did not last long and he was soon reinstated. Although Sobukwe was secretary of the ANC’s Standerton branch from 1950 to 1954, he was not directly involved in mainstream ANC activities.

In 1954 Sobukwe moved to Johannesburg, where he became a lecturer in African Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand – a job which earned him the nickname ‘the Prof’. He settled in Mofolo, Soweto, where he joined a branch of the ANC. Sobukwe became editor of The Africanist in 1957 and soon began to criticise the ANC for allowing itself to be dominated by what he termed 'liberal-left-multi-racialists'. In 1958 Sobukwe completed his Honours dissertation at Wits entitled “A collection of Xhosa Riddles”.

Politically, Sobukwe was strongly Africanist, believing that the future of South Africa should be in the hands of Black South Africans. As a result of his septicism towards the multi-racial path the ANC was following, Sobukwe was instrumental in initiating an Africant breakaway from the ANC in 1958, which led to the birth of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). He stated:

“In 1955 the Kilptown Charter was adopted, which according to us, is irreconcilable conflict with the 1949 Programme seeing that it claims land no longer Africa, but is auctioned for sale to all who live in this country. We have come to the parting of the ways and we are here and now giving notice that we are disassociating ourselves from the ANC as it is constituted at present in the Transvaal.”

At the PAC’s inaugural congress, held in Orlando from 4 to 6 April 1959, Sobukwe was unanimously elected the party’s first President. Sobukwe's eloquence as a public speaker, his intelligence and commitment to his cause soon established him as natural leader, and helped him rally support for the PAC. Sobukwe’s opposition to ‘multi-racialism’ in favour of ‘non-racialism’ is apparent in an extract from his inaugural speech at the PAC launch in 1959.

A week after the ANC announced its anti-pass campaign in December 1959, the PAC announced that it was planning to initiate a campaign against the pass laws with the aim to free South Africa by 1963. On 16 March 1960, Sobukwe wrote to the Commissioner of Police, Major General Rademeyer, stating that the PAC would be holding a five-day, non-violent, disciplined, and sustained protest campaign against pass laws, starting on 21 March. On 21 March 1960, at the launch of the PAC’s anti-pass campaign, Sobukwe resigned from his post as lecturer at the University of Witwatersrand. He made last-minute arrangements for the safety of his family and left his home in Molofo. He intended to give himself up for arrest at the Orlando Police Station in the hope that his actions would inspire other Black South Africans. Along the eight kilometre walk to the police station, small groups of men joined him from neighbouring areas like Phefeni, Dube and Orlando West. As the small crowd approached the station, most of the marchers, including Sobukwe, were arrested and charged with sedition. When an estimated group of 5000 marchers reached Sharpeville police station, the police opened fire killing 69 people and injuring 180 others in what became known as the Sharpeville Massacre.

An order was issued on 25 March 1960 for the banishment of Sobukwe to the Driefontein Native Trust Farm, Vryburg District, [Northern Cape, now North West Province]. At the time, Sobukwe was living in Mafolo Bantu Township, Johannesburg, Transvaal [now Gauteng].

The documentation on the banishment noted that Sobukwe and Leballo had both been arrested and were awaiting trial “but it [was] necessary to have a banishment order in hand just in case they are released.” Sobukwe never spent time in banishment as he was sentenced to imprisonment for incitement.

On 4 May 1960 Sobukwe was sentenced to three years in prison for inciting Africans to demand the repeal of the pass laws. He refused to appeal against the sentence, as well as the aid of an attorney, on the grounds that the court had no jurisdiction over him as it could not be considered either a court of law or a court of justice. At the end of his three-year sentence on 3 May 1963, Parliament enacted a General Law Amendment Act. The Act included what was termed the 'Sobukwe Clause', which empowered the Minister of Justice to prolong the detention of any political prisoner indefinitely. Subsequently, Sobukwe was moved to Robben Island, where he remained for an additional six years. The Clause was never used to detain anyone else. The Sobukwe Clause was renewed every year – when it was due to expire on 30 June 1965, the government renewed it.

While on Robben Island, Sobukwe was kept in solitary confinement – his living quarters were separate from the main prison and he had no contact with any other prisoners. He was, however, allowed access to books and civilian clothes. As a result, Sobukwe spent much of his time studying, and he obtained a degree in Economics from the University of London. In 1964 Sobukwe was offered a job by the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and the Montgomery Fellowship for Foreign Aid in the US. He applied to leave the country with his family to take up the employment but was denied permission by the Minister of Justice, John Vorster.

Sobukwe was released from prison in May 1969 and was banished to Galeshewe in Kimberley, where he was joined by his family. However, he remained under twelve-hour house arrest and his banning order prohibited him from participating in any political activity. In 1970 Sobukwe successfully applied for a teaching post at the University of Wisconsin in the US, but the Apartheid government refused his request for a passport despite assurances that he would be given a visa by the US government. When he applied to leave South Africa permanently together with his family in 1971, the South African government again refused to give him permission.

While the restrictions kept him under house arrest and denied him permission to leaving South Africa, he was permitted to attend family gatherings outside Kimberley. For instance, in July 1973 Sobukwe was granted permission to leave Kimberley to visit his son Dalindyebo, who had been hospitalised in Johannesburg. In June 1974 Sobukwe spent three days in Johannesburg visiting his wife, who underwent an operation at a hospital in Johannesburg. Finally, in 1975, Sobukwe’s mother died and he applied to the Chief Magistrate of Kimberley for a permit to leave the town in order to attend the funeral. He was granted permission on condition that he report to the police station upon arrival and departure, and that he return to Kimberley by midnight on Friday 9 May 1975, a day after the funeral.

Sobukwe began studying Law while he was under house arrest. He completed his articles in Kimberley, and established his own law firm in 1975. The government’s Department of Justice initially denied him permission to enter the courts, but reversed the decision and withdrew the prohibition after the government relaxed a clause that banned Sobukwe from entering a court of law except as an accused or as a witness. However, newspapers were not allowed to quote him when he argued in court.

Shortly after opening his law practice, Sobukwe fell ill. In July 1977 he applied for permission to go for medical treatment in Johannesburg. Benjamin Pogrund, a close family friend, intervened and on 9 September Sobukwe was allowed to leave Kimberley for Johannesburg under strict conditions. He was diagnosed with lung cancer and his condition was deemed serious. Consequently, Sobukwe was transferred to Groote Schuur hospital in Cape Town. While he was in the hospital the security branch instructed the medical staff not to permit any visitors to visit him except his family.

Sobukwe’s wife applied for permission from the Cape magistrate for him to stay with a family friend, Bishop Pat Matolengwe. After deliberate delays by the government, on 14 October he was temporality discharged and Bishop Matolengwe took him from the hospital. Sobukwe was sent back to Kimberley, from he was due to travel back to Cape Town for another round of treatment. Each time he left Kimberley, he had to report to the police station – which he also had to do when he arrived at or left Cape Town.

The government deliberately made it harder for Sobukwe to receive treatment by insisting that he should comply with the conditions of his restrictions, despite his evidently failing health. On 27 February 1978 Sobukwe died from lung complications at Kimberley General Hospital. His funeral was held on 11 March 1978 and he was buried in Graaff-Reinet. Today, he remains a celebrated political figure in the struggle for a democratic South Africa.

Biography Retrieved from South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/robert-mangaliso-sobukwe

Biography of the Week: Robert Sobukwe

Names: Sobukwe, Robert Mangaliso

Born: 5 December 1924, Graaff-Reinet, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Died: 27 February 1978, Kimberley, Cape Province, South Africa

In summary: Teacher, lecturer, lawyer, Fort Hare University SRC President, secretary of the ANC branch in Standerton, founding member and first president of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and Robben Island prisoner.

Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe was born to Hubert and Angelina Sobukwe on 5 December 1924 at Graaff-Reinet, Cape Province. He was the youngest of five boys and one girl. His father worked as a municipal labourer and a part-time woodcutter, his mother as a domestic worker and cook at a local hospital.

Sobukwe was exposed to literature at an early age by his oldest brother. His earliest education was at a mission school in Graaf Reinet. After completing Standard 6 he enrolled for a Primary Teachers’ Training Course for two years, but he was not given a teaching post. He then went back to high school, enrolling at the Healdtown Institute, where he spent six years studying with financial assistance provided by George Caley, the school’s headmaster, and completed his Junior Certificate (JC) and matric. Sobukwe’s schooling was briefly interrupted in 1943 when he was admitted to a hospital suffering from tuberculosis.

After completing his schooling he received a bursary from the Department of Education and an additional loan from the Bantu Welfare Trust, which enabled him to enrol at Fort Hare University for tertiary education in 1947. Sobukwe registered for a BA majoring in English, Xhosa and Native Administration. His keen interest in literature continued and became more focused on poetry and drama.

Sobukwe noted that before going to Fort Hare, he was not very interested in politics. It was his study of Native Administration that aroused his interest in politics. This new focus was fuelled by the influence of one of his lecturers, Cecil Ntloko, a follower of the All African Convention (AAC). Fort Hare was also the institution in which generations of young Black South Africans and Black students from other African countries were exposed to politics. These influences combined to make Sobukwe more politically active.

Biography Retrieved from South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/robert-mangaliso-sobukwe

Born: 5 December 1924, Graaff-Reinet, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Died: 27 February 1978, Kimberley, Cape Province, South Africa

In summary: Teacher, lecturer, lawyer, Fort Hare University SRC President, secretary of the ANC branch in Standerton, founding member and first president of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and Robben Island prisoner.

Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe was born to Hubert and Angelina Sobukwe on 5 December 1924 at Graaff-Reinet, Cape Province. He was the youngest of five boys and one girl. His father worked as a municipal labourer and a part-time woodcutter, his mother as a domestic worker and cook at a local hospital.

Sobukwe was exposed to literature at an early age by his oldest brother. His earliest education was at a mission school in Graaf Reinet. After completing Standard 6 he enrolled for a Primary Teachers’ Training Course for two years, but he was not given a teaching post. He then went back to high school, enrolling at the Healdtown Institute, where he spent six years studying with financial assistance provided by George Caley, the school’s headmaster, and completed his Junior Certificate (JC) and matric. Sobukwe’s schooling was briefly interrupted in 1943 when he was admitted to a hospital suffering from tuberculosis.

After completing his schooling he received a bursary from the Department of Education and an additional loan from the Bantu Welfare Trust, which enabled him to enrol at Fort Hare University for tertiary education in 1947. Sobukwe registered for a BA majoring in English, Xhosa and Native Administration. His keen interest in literature continued and became more focused on poetry and drama.

Sobukwe noted that before going to Fort Hare, he was not very interested in politics. It was his study of Native Administration that aroused his interest in politics. This new focus was fuelled by the influence of one of his lecturers, Cecil Ntloko, a follower of the All African Convention (AAC). Fort Hare was also the institution in which generations of young Black South Africans and Black students from other African countries were exposed to politics. These influences combined to make Sobukwe more politically active.

Biography Retrieved from South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/robert-mangaliso-sobukwe

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

My Blackness is the beauty of this land

my blackness,

tender and strong, wounded and wise,

my blackness:

I, drawling black grandmother, smile muscular and sweet,

unstraightened white hair soon to grow in earth,

work-thickened hand thoughtful and gentle on grandson’s head,

my heart is bloody-razored by a million memories’ thrall:

remembering the crook-necked cracker who spat

on my naked body,

remembering the splintering of my son’s spirit

because he remembered to be proud

remembering the tragic eyes in my daughter’s

dark face when she learned her color’s meaning,

and my own dark rage a rusty knife with teeth to gnaw

my bowels,

my agony ripped loose by anguished shouts in Sunday’s

humble church,

my agony rainbowed to ecstasy when my feet oversoared

Montgomery’s slime,

ah, this hurt, this hate, this ecstasy before I die,

and all my love a strong cathedral!

My Blackness is the beauty of this land!

Lay this against my whiteness, this land!

Lay me, young Brutus stamping hard on the cat’s tail,

gutting the Indian, gouging the nigger,

booting Little Rock’s Minniejean Brown in the buttocks and boast,

my sharp white teeth derision-bared as I the conqueror crush!

Skyscraper-I, white hands burying God’s human clouds beneath

the dust!

Skyscraper-I, slim blond young Empire

thrusting up my loveless bayonet to rape the sky,

then shrink all my long body with filth and in the gutter lie

as lie I will to perfume this armpit garbage,

While I here standing black beside

wrench tears from which the lies would suck the salt

to make me more American than America…

But yet my love shall civilize this land,

this land’s salvation.

By: Lance Jeffers

tender and strong, wounded and wise,

my blackness:

I, drawling black grandmother, smile muscular and sweet,

unstraightened white hair soon to grow in earth,

work-thickened hand thoughtful and gentle on grandson’s head,

my heart is bloody-razored by a million memories’ thrall:

remembering the crook-necked cracker who spat

on my naked body,

remembering the splintering of my son’s spirit

because he remembered to be proud

remembering the tragic eyes in my daughter’s

dark face when she learned her color’s meaning,

and my own dark rage a rusty knife with teeth to gnaw

my bowels,

my agony ripped loose by anguished shouts in Sunday’s

humble church,

my agony rainbowed to ecstasy when my feet oversoared

Montgomery’s slime,

ah, this hurt, this hate, this ecstasy before I die,

and all my love a strong cathedral!

My Blackness is the beauty of this land!

Lay this against my whiteness, this land!

Lay me, young Brutus stamping hard on the cat’s tail,

gutting the Indian, gouging the nigger,

booting Little Rock’s Minniejean Brown in the buttocks and boast,

my sharp white teeth derision-bared as I the conqueror crush!

Skyscraper-I, white hands burying God’s human clouds beneath

the dust!

Skyscraper-I, slim blond young Empire

thrusting up my loveless bayonet to rape the sky,

then shrink all my long body with filth and in the gutter lie

as lie I will to perfume this armpit garbage,

While I here standing black beside

wrench tears from which the lies would suck the salt

to make me more American than America…

But yet my love shall civilize this land,

this land’s salvation.

By: Lance Jeffers

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Ethics Alive Symposium 2013

The Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg and the Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics invite you to attend an evening of reflection and debate on

Healthcare Professionals and Social Conscience

Date: Thursday 14 March 2013

Time: 17h30

Venue: Hospital Auditorium, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the

Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 7 York Road, Parktown, Johannesburg

Proceedings

17h30 Welcome Cocktails

18h00 Formal Programme: Chaired by Professor Phumzile Hlongwa, Head

of School: Oral Health Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Wits University

Opening of Symposium: Professor Loyiso Nongxa, Vice Chancellor: University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

Symposium

Healthcare Professionals and Social Conscience

Dr Jeff Blackmer (Executive Director: Office of Ethics, Professionalism and International Affairs, Canadian Medical Association)

Conscience, Medicine and Corruption

Dr Anthony Egan (Lecturer: Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics)

The Progressive Realisation of the Right to Access Healthcare

Mr Kayum Ahmed (CEO: South African Human Rights Commission)

Panel Discussion

Presentation of Undergraduate Bioethics Competition Prizes

Closure: Professor Ahmed Wadee, Dean of the Faculty of Health

Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

20h00 Finger Supper

RSVP: Kurium Govender of the Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics

Tel: 011 717 2190

Email: Kurium.Govender@wits.ac.za

By: 2 March 2013

CPD ACCREDITED

Healthcare Professionals and Social Conscience

Date: Thursday 14 March 2013

Time: 17h30

Venue: Hospital Auditorium, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the

Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 7 York Road, Parktown, Johannesburg

Proceedings

17h30 Welcome Cocktails

18h00 Formal Programme: Chaired by Professor Phumzile Hlongwa, Head

of School: Oral Health Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Wits University

Opening of Symposium: Professor Loyiso Nongxa, Vice Chancellor: University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

Symposium

Healthcare Professionals and Social Conscience

Dr Jeff Blackmer (Executive Director: Office of Ethics, Professionalism and International Affairs, Canadian Medical Association)

Conscience, Medicine and Corruption

Dr Anthony Egan (Lecturer: Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics)

The Progressive Realisation of the Right to Access Healthcare

Mr Kayum Ahmed (CEO: South African Human Rights Commission)

Panel Discussion

Presentation of Undergraduate Bioethics Competition Prizes

Closure: Professor Ahmed Wadee, Dean of the Faculty of Health

Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

20h00 Finger Supper

RSVP: Kurium Govender of the Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics

Tel: 011 717 2190

Email: Kurium.Govender@wits.ac.za

By: 2 March 2013

CPD ACCREDITED

PARI Postgraduate scholarships available

The Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI) invites applications for postgraduate and postdoctoral scholarships for study at the University of the Witwatersrand.

PARI-Nedbank Scholarship Programme: Masters scholarships are available under this prestigious programme which supports talented South African students interested in researching the histories, cultures and economics of public sector institutions.

PARI-NRF PhD and postdoctoral scholarships are available under PARI’s research programme on social change in South Africa. Successful applicants to this programme will join a growing body of talented researchers undertaking innovative research on social dynamics in the country and the implications for governance.

Applications close 31 January 2013. See the website for further details or email sarahmg@pari.org.za.

PARI-Nedbank Scholarship Programme: Masters scholarships are available under this prestigious programme which supports talented South African students interested in researching the histories, cultures and economics of public sector institutions.

PARI-NRF PhD and postdoctoral scholarships are available under PARI’s research programme on social change in South Africa. Successful applicants to this programme will join a growing body of talented researchers undertaking innovative research on social dynamics in the country and the implications for governance.

Applications close 31 January 2013. See the website for further details or email sarahmg@pari.org.za.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Biography of the Week: Sam Nujoma

Sam Nujoma is commonly referred to as ‘the father of the nation' and, indeed, his personality and achievements tower over Namibian politics and public life. Nujoma is the central figure in the liberation struggle that brought independence to Namibia and he is equally central to the policies and practices that have shaped Namibia since then.

Nujoma was born in 1929 in Etunda in what was then called Owamboland. He attended a Finnish Lutheran mission school at Okahao and completed grade eight, which was as high as was possible for black Namibians in those days. In 1946, he moved to Walvis Bay where he worked in a store and then at a whaling station before moving to Windhoek to work as a cleaner on the South African Railways in 1959. In 1956 he visited Cape Town, where he met some of the Namibians working there who were opposed to South African policies in Namibia (then South West Africa) and wanted it to be placed under United Nations trusteeship. Soon afterwards they formed the Ovamboland People's Congress, forerunner of the Ovamboland People's Organisation (OPO), itself the forerunner of the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO), the party that Nujoma eventually led to power in independent Namibia in 1990. Nujoma was the first and only president of the OPO.

After the shootings at Windhoek's Old Location in December 1959, political repression in Namibia increased and, with Nujoma facing the likelihood of being ‘internally exiled' to Owamboland, the OPO decided that he should join the other Namibians in exile who were lobbying the UN on behalf of the anti-colonial cause for Namibia. Nujoma left Namibia in February 1960 and, by various means, made his way to Tanzania, which was still the British colony of Tanganyika. There he received permission to address the UN Committee on South West Africa in New York and, while en route, visited the independent African countries of Ghana and Liberia. It was during this time that the decision was taken to give the OPO a national character by changing its name to the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO), with Nujoma as its first, and thus far only, president. In New York, Nujoma addressed a number of UN committees, a forerunner of his involvement in international diplomacy that would intensify with the years.

With strong support from Julius Nyerere, the future leader of independent Tanzania, Nujoma established SWAPO's headquarters in Dar es Salaam, where other exiled Namibians began to join him. Thanks to their efforts, SWAPO gained important support and status, especially when the Organisation of African Unity recognized SWAPO in 1965. Nujoma worked tirelessly for SWAPO, setting up offices in various countries around the world, achieving significant diplomatic success when, in 1971, he was the first leader of an African liberation movement to address the UN Security Council. There was further success when in 1976 the UN General Assembly recognized SWAPO as ‘sole and authentic representative of the Namibian people'.

As the internal and external pressures on the South African regime increased, it began to negotiate over Namibia with the UN Security Council and its five-member Western Contact Group, comprising Britain, Canada, France, the United States, and West Germany. Nujoma led the SWAPO delegation in these negotiations, which eventually led to UN Security Council Resolution 435 and a comprehensive plan and set of measures for bringing Namibia to internationally recognized independence. With the connivance of the USA, South Africa managed to delay developments for nearly a decade until, finally, Resolution 435 was implemented on 1st April 1989. Nujoma returned to Namibia in triumph on 14th September of that year and led the successful SWAPO election campaign for the Constituent Assembly, which became the first parliament of independent Namibia and elected Nujoma as the first president of the country. Nujoma eventually served three terms, gaining larger majorities with each election, after the constitution was amended to allow him to stand for an extra term.

At independence, Namibia was gravely divided as a result of a century of colonialism, dispossession, and racial discrimination, compounded by armed struggle and propaganda. For instance, SWAPO had been so demonised by the colonial media and by official pronouncements that most white people, as well as many members of other groups, regarded the movement with the deepest fear, loathing, and suspicion. One of Nujoma's earliest achievements was to proclaim the policy of ‘national reconciliation', which aimed to improve and harmonise relations amongst Namibia's various racial and ethnic groups. Generally, under his presidency, Namibia made steady if unspectacular economic progress, maintained a democratic system with respect for human rights, observed the rule of law, and worked steadily to eradicate the heritage of apartheid in the interests of developing a non-racial society.

Biography Retrieved from http://www.namibian.org/travel/namibia/history/sam_nujoma.html

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Why The Term 'Black'?

Judge Boshof: But why do you refer to you people as blacks? Why not brown people? I mean you people are more brown than black.

Biko: In the same way as I think white people are more pink and yellow and pale than white.

Judge Boshoff: Quiet…but now why do you not use the word brown then?

Biko: No, I think really, historically, we have been defined as black people, and when we reject the term non-white and take upon ourselves the right to call ourselves what we think we are, we have got available in front of us a whole number of alternatives, starting from natives to Africans to Kaffirs to Bantu to Non-whites and so on, and we choose this one precisely because we feel it is most accommodating.

Judge Boshoff: Yes but then you put your foot into it, you use black which really connotates dark forces over the centuries?

Biko: This is correct, precisely because it has been used in that context our aim is to choose it for reference to us and elevate it to a position where we can look upon ourselves positively; because no matter whether we choose to be called brown, you are still going to get reference to blacks in an inferior sense in literature and in speeches by white racists or white persons in our society.

Extract from Steve Biko’s evidence in the BPC-SASO trial given in the first week of May 1976. Retreived from:

S. Biko. 2004. I Write What I Like. Johannesburg: Picador Africa

Biko: In the same way as I think white people are more pink and yellow and pale than white.

Judge Boshoff: Quiet…but now why do you not use the word brown then?

Biko: No, I think really, historically, we have been defined as black people, and when we reject the term non-white and take upon ourselves the right to call ourselves what we think we are, we have got available in front of us a whole number of alternatives, starting from natives to Africans to Kaffirs to Bantu to Non-whites and so on, and we choose this one precisely because we feel it is most accommodating.

Judge Boshoff: Yes but then you put your foot into it, you use black which really connotates dark forces over the centuries?

Biko: This is correct, precisely because it has been used in that context our aim is to choose it for reference to us and elevate it to a position where we can look upon ourselves positively; because no matter whether we choose to be called brown, you are still going to get reference to blacks in an inferior sense in literature and in speeches by white racists or white persons in our society.

Extract from Steve Biko’s evidence in the BPC-SASO trial given in the first week of May 1976. Retreived from:

S. Biko. 2004. I Write What I Like. Johannesburg: Picador Africa

Monday, January 14, 2013

The Definition of Black Consciousness

This is the paper produced for a SASO Leadership Training Course in December 1971 by Bantu Stephen Biko.

We have defined blacks as those who are by law or tradition politically, economically and socially discriminated against as a group in the South African society and identifying themselves as a unit in the struggle towards the realization of their aspirations. This definition illustrates to us a number of things:

1. Being black is not a matter of pigmentation - being black is a reflection of a mental attitude.

2. Merely by describing yourself as black you have started on a road towards emancipation, you have committed yourself to fight against all forces that seek to use your blackness as a stamp that marks you out as a subservient being.

From the above observations therefore, we can see that the term black is not necessarily all-inclusive, i.e. the fact that we are all not white does not necessarily mean that we are all black. Non-whites do exist and will continue to exist for quite a long time. If one's aspiration is whiteness but his pigmentation makes attainment of this impossible, then that person is a non-white. Any man who calls a white man "baas", any man who serves in the police force or security branch is ipso facto a non-white. Black people - real black people - are those who can manage to hold their heads high in defiance rather than willingly surrender their souls to the white man.

Briefly defined therefore, Black Consciousness is in essence the realization by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their oppression - the blackness of their skin - and to operate as a group in order to rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude. It seeks to demonstrate the lie that black is an aberration from the "normal" which is white. It is a manifestation of a new realization that by seeking to run away from themselves and to emulate the white man, black are insulting the intelligence of whoever created them black. Black Consciousness therefore takes cognizance of the deliberateness of the God's plan in creating black people black. It seeks to infuse the black community with a new-found pride in themselves, their efforts, their value systems, their culture, their religion and their outlook to life.

The interrelationship between the consciousness of the self and the emancipatory programme is of a paramount importance. Blacks no longer seek to reform the system because so doing implies acceptance of the major points around which the system revolves. Blacks are out to completely transform the system and to make of it what they wish. Such a major undertaking can only be realized in an atmosphere where people are convinced of the truth inherent in their stand. Liberation therefore is of paramount importance in the concept of Black Consciousness, for we cannot be conscious of ourselves and yet remain in bondage. We want to attain the envisioned self which is a free self.

The surge towards Black Consciousness is a phenomenon that has manifested itself throughout the so-called Third World. There is no doubt that discrimination against the black man the word over fetches its origin from the exploitative attitude of the white man. Colonization of white countries by whites has throughout history resulted in nothing more than sinister than mere cultural or geographical fusion at worst, or language bastardization at best.

It is true that the history of weaker nations is shaped by bigger nations, but nowhere in the world today do we see whites exploiting whites on scale even remotely similar to what is happening in South Africa. Hence, one is forced to conclude that it is not coincidence that black people are exploited. It was a deliberate plan which has culminated in even so-called black independent countries not attaining any real independence.

With this background in mind we are forced, therefore, to believe that it is a case of haves against have-nots where whites have been deliberately made haves and black have-nots.

There is for instance no worker in the classical sense among whites in South Africa, for even the most downtrodden white worker still has a lot lose if the system is changed. He is protected by several laws against competition at work from the majority. He has a vote and he uses it to return the Nationalist Government to power because he sees them as the only people who, through job reservation laws, are bent on looking after his interests against competition with the "Natives".

It should therefore be accepted that analysis of our situation in terms of one's colour at once takes care of the greatest single determinant for political action - i.e. colour - while also validly describing the blacks as the only real workers in South Africa. It immediately kills all suggestions that there could ever be effective rapport between the real workers, i.e. blacks, and the privileged white workers, since we have shown that the latter are the greatest supporters of the system.

True enough, the system has allowed so dangerous an anti-black attitude to build up amongst whites, who are economically nearest to the blacks, demonstrate the distance between themselves and the blacks by an exaggerated reactionary attitude towards blacks. Hence the greatest anti-black feeling is to be found amongst the very poor whites whom the Class Theory calls upon to be with black workers in the struggle for emancipation. This is the kind of twisted logic that Black Consciousness approach seeks to eradicate.

In terms of the Black Consciousness approach we recognize the existence of one major force in South Africa. This is White Racism. It is the one force against which all of us are pitted. It works with unnerving totality, featuring both on the offensive and in our defence. Its greatest ally to date has been the refusal by us to progressively lose ourselves in a world of colourlessness and amorphous common humanity, whites are deriving pleasure and security in entrenching white racism and further exploiting the minds and bodies of the unsuspecting black masses. Their agents are ever present amongst us, telling that it is immoral to withdraw into a cocoon, that dialogue is the answer to our problem and that it is unfortunate that there is white racism in some quarters but you must that things are changing.

These in fact are the greatest racists for they refuse to credit us any intelligence to know what we want. Their intentions are obvious; they want to be barometers by which the rest of the white society can measure feelings in the black world. This then is what makes us believe that white power presents itself as a totality not only provoking us but also controlling our response to the provocation. This is an important point to note because it is often missed by those who believe that there are a few good whites. Sure there are few good whites just as much as there are a few bad blacks.

However what we are concerned here with is group attitudes and group politics. The exception does not make a lie of a rule - it merely substantiates it. The overall analysis therefore, based on the Hegelian theory of dialectic materialism, is as follows. That since the thesis is a white racism there can only be one valid antithesis, i.e. a solid black unity, to counterbalance the scale. If South Africa is to be a land where black and white live together in harmony without fear of group exploitation, it is only when these two opposites have interplayed and produced a viable synthesis of ideas and modus vivendi. We can never wage any struggle without offering a strong counterpoint to the white racism that permeate our society so effectively.

One must immediately dispel the thought that Black Consciousness is merely a methodology or a means towards an end. What Black Consciousness seeks to do is to produce at the output end of the process real black people who do not regard themselves as the appendages to white society. This truth cannot be reserved. We do not need to apologize for this because it is true that the white systems have produced throughout the world a number of people who are not aware that they too are people. Our adherence to values that we set for ourselves can also not be reversed because it will always be a lie to accept white values as necessarily the best. The fact that a synthesis may be attained only relates to adherence to power politics. Someone somewhere along the line will be forced to accept the truth and here we believe that ours is the truth.

The future of South Africa in the case where blacks adopt Black Consciousness is the subject for concern especially among initiates. What do we do when have attained our Consciousness ? Do we propose to kick whites out? I believe personally that the answers to these questions ought to be found in the SASO Policy Manifesto and in our analysis of the situation in South Africa. We have defined what we mean by true integration and the very fact that such a definition exists does illustrate what our standpoint is. In any case we are much more concerned about what is happening now, than will happen in the future. The future will always be shaped by the sequence of present-day events.

The importance of black solidarity to the various segments of the black community must not be understated. There have been in the past a lot of suggestions that there can be no viable unity amongst blacks because they hold each other in contempt. Coloureds despise Africans because they (the former), by their proximity to the Africans, may lose the chances of assimilation into the white world. Africans despise the Coloureds and Indians for a variety of reasons. Indians not only despise Africans but in many instances also exploit the Africans in job and shop situations. All these stereotype attitudes have led to mountainous inter-group suspicions amongst the blacks.

What we should at all times look at is the fact that:

1. We are all oppressed by the same system.

2. That we are oppressed to varying degrees is a deliberate design to stratify us not only socially but also in terms of the enemy's aspirations.

3. Therefore it is to be expected that in terms of the enemy's plan there must be this suspicion and that if we are committed to the problem of emancipation to the same degree it is part of our duty to bring to the black people the deliberateness of the enemy's subjugation scheme.

4. That we should go on with our programme, attracting to it only committed people and not just those eager to see an equitable distribution of groups amongst our ranks. This is a game common amongst liberals. The one criterion that must govern all our action is commitment.

Further implications of Black Consciousness are to do with correcting false images of ourselves in terms of culture, Education, Religion, Economics. The importance of this also must not be understated. There is always an interplay between the history of people i.e. the past, their faith in themselves and hopes for their future. We are aware of the terrible role played by our education and religion in creating amongst us a false understanding of ourselves. We must therefore work out schemes not only to correct this, but further to be our own authorities rather than wait to be interpreted by others.

Whites can only see us from the outside and as such can never extract and analyze the ethos in the black community. In summary therefore one need only refer this house to the SASO Policy Manifesto which carries most of the salient points in the definition of the Black Consciousness. I wish to stress again the need for us to know very clearly what we mean by certain terms and what our understanding is when we talk of Black Consciousness.

Article from S. Biko. 2004. I Write What I Like. Johannesburg: Picador Africa.

Friday, January 11, 2013

Afrika You Raised Me

Afrika you raised me

Afrika embrace me

Pain and suffering, hardship doesn’t faze me

Afrika, Protector, you never let them erase me

So here I stand

Feet soaked deep in blood shed in our land

But I will walk hand in hand,

with the wind and the rain,

my companions and fellow soldiers against the pain

Although I stumble over poverty, AIDS, corruption again and again

It’s the spirit of Ubuntu in my people that keeps me sane

Afrika you taught me that no monetary value can be placed on life

Blessed me with ability to find joy in times of strife

Afrika I am strong,

for Afrika you raised me,

continue to embrace me, Afrika!

By: Gcinumzi Nkohla and Sinalo Dlanga

Afrika embrace me

Pain and suffering, hardship doesn’t faze me

Afrika, Protector, you never let them erase me

So here I stand

Feet soaked deep in blood shed in our land

But I will walk hand in hand,

with the wind and the rain,

my companions and fellow soldiers against the pain

Although I stumble over poverty, AIDS, corruption again and again

It’s the spirit of Ubuntu in my people that keeps me sane

Afrika you taught me that no monetary value can be placed on life

Blessed me with ability to find joy in times of strife

Afrika I am strong,

for Afrika you raised me,

continue to embrace me, Afrika!

By: Gcinumzi Nkohla and Sinalo Dlanga

Wednesday, January 09, 2013

Sir Seretse Khama: The Nationalist Hero

Fit To Rule