Congratulations to the following winners of the FrankTalk Blog Competition on "What Does It Mean To be A South African?"

1. Nompumemlelo Zinhle Manzini

2. Phetego Kgomo

3. Tshepo Ntokoane

4. K.C Monareng

5. Mpho Mabala

Each of the winners gets a copy of The Steve Biko Memorial Lectures book.

To claim your prize, please send us your full address (where to post your book) via email at dibuseng@sbf.org.za or call 011 403 0310. Alternatively, you can inbox us your address via Facebook at The Steve Biko Foundation.

Many thanks once again to everyone who contributed an article to the FrankTalk blog.

Monday, April 29, 2013

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Blacks Don’t Need White People

By Gcobisa Silwana

On the 19th of April 2013, Azania Matiwane’s article “Blacks need white people” http://www.timeslive.co.za/ilive/2013/04/19/blacks-need-white-people-ilive was published on the times live. The following is my response to him.

Matiwane wrote: “On the May 20, 2013, African Union (AU) will be celebrating 50 years of Africa’s independence, alas albeit there would be no reason for celebration for Africa’s people as they continue to experience violent civil wars, corruption, poverty and neglect at the hands of weak leadership by African politicians. Therefore, celebrating the independence of Africa will only be confined to the elite, the African politicians who continue to loot resources of African nations for their respective families and friends under guise of their respective people.”

Mr. Matiwane, while this is true, it is important to keep mindful of what happened in Africa. Remember, white people came to Africa without invitation and as Africans, our natural response was to welcome them. They then abused our ubuntu and took away everything we had, including our self-respect; and then turned us against each other.

Slowly, they forced their ways onto us, and ridiculed our belief in Qamata. We then became known as kaffirs, non-believers. They killed our spirit. As if that was not enough, they made us beg for what was originally ours. We became their slaves. They instilled so much fear in us that we had to accept their dictatorship to survive.

In their eyes we were less human; the saddest part is that we ended up believing this, and some of us still do.

You speak about our attachment to white philosophy. Do you not know of Steve Biko? He was a South African philosopher whose message was that African people should not see themselves inferior or superior to white people. His message was that, even though we may be different, we are all people and we are all equal.

He was killed by the same people that you think we need, because they wouldn’t accept this truth.

I will not pretend that I know what happens in the Prime Minister of Britain’s office – so I will not compare it with Zuma’s office. Anyway, it would almost be the same as asking a pear why it does not taste like a banana. What I can say, however, is that colonialism was the perfect recipe for creating greedy, selfish people. If you deprive somebody of food long enough, the moment they get it, they will want to keep everything to themselves because they do not want to be deprived again. I am not applauding this behaviour – I am only saying that it is something that should be expected.

There are many things that need to be considered. And one of them is that we fought for freedom without properly defining what it is. The circumstances that we were under made us believe that freedom meant walking around without a dompas, and dining in white people’s restaurants etc. We were desperate!

We now walk around without a dompas and we eat in white people’s restaurants. But are we free?

To be honest, to some extent I understand why people like Mogabe and Malema do what they do. They feel Africa’s pain, deeply. But we cannot fight fire with fire. History has taught us that.

You say black people need white people to teach them to care for the environment. Whose factories dump waste products into the ocean?

Don’t forget that while white people got ‘education’ black people got ‘Bantu education’. This was the colonialist’s plan to keep black people dependent on them. And my brother, you fell for it!

I agree that practices such as Ukuthwala are harmful and should not be accepted – but you seem to forget that all cultures (including white people’s culture) have practices that are rather harmful, but some things are not spoken about. I have spent many years amongst white people and I learnt that they do not make a habit of mocking themselves in the presence of black people. They know that they do not have to please us, and we need to know this too.

We could never erase what happened in the past, nor can we forget it. But we have cried for too long, and if we don’t stop, we may never heal!

It would be silly of us to destroy white suburbs and build huts. But we should be able to enjoy what was created on African soil because colonialism did not allow us to develop Africa our own way. Who knows what we would have come up with? I get the feeling it would have been beautiful and free of toxic chemicals!

We do not need physical change; we need a change in consciousness!

I think what our forefathers really wanted was a country where all people are respected and treated equally regardless of their race. A country where an architect values the ‘uneducated’ bricklayer and the bricklayer knows his value. We all know that they are both necessary to making the project a reality.

Sadly, in 2013, the bricklayer still thinks he is nothing without the architect – and the architect benefits from this. We need a country that encourages the bricklayer to constantly aim to improve himself. He should know his value, and not be satisfied with doing the same work for 20 years. It was not by chance that we were all given a brain!

As long as people like you keep saying things like these, white people will never respect black people, and black people will keep on believing that they are inferior. You might get a pat on the back from your white colleagues (who, by the way, see you as a black man on their leash) but your kind of thinking is not beneficial to our people.

Vuka mntakwethu!

This article was first published by Times Live. Please find the original article at http://www.timeslive.co.za/ilive/2013/04/23/black-people-don-t-need-white-people-ilive

On the 19th of April 2013, Azania Matiwane’s article “Blacks need white people” http://www.timeslive.co.za/ilive/2013/04/19/blacks-need-white-people-ilive was published on the times live. The following is my response to him.

Matiwane wrote: “On the May 20, 2013, African Union (AU) will be celebrating 50 years of Africa’s independence, alas albeit there would be no reason for celebration for Africa’s people as they continue to experience violent civil wars, corruption, poverty and neglect at the hands of weak leadership by African politicians. Therefore, celebrating the independence of Africa will only be confined to the elite, the African politicians who continue to loot resources of African nations for their respective families and friends under guise of their respective people.”

Mr. Matiwane, while this is true, it is important to keep mindful of what happened in Africa. Remember, white people came to Africa without invitation and as Africans, our natural response was to welcome them. They then abused our ubuntu and took away everything we had, including our self-respect; and then turned us against each other.

Slowly, they forced their ways onto us, and ridiculed our belief in Qamata. We then became known as kaffirs, non-believers. They killed our spirit. As if that was not enough, they made us beg for what was originally ours. We became their slaves. They instilled so much fear in us that we had to accept their dictatorship to survive.

In their eyes we were less human; the saddest part is that we ended up believing this, and some of us still do.

You speak about our attachment to white philosophy. Do you not know of Steve Biko? He was a South African philosopher whose message was that African people should not see themselves inferior or superior to white people. His message was that, even though we may be different, we are all people and we are all equal.

He was killed by the same people that you think we need, because they wouldn’t accept this truth.

I will not pretend that I know what happens in the Prime Minister of Britain’s office – so I will not compare it with Zuma’s office. Anyway, it would almost be the same as asking a pear why it does not taste like a banana. What I can say, however, is that colonialism was the perfect recipe for creating greedy, selfish people. If you deprive somebody of food long enough, the moment they get it, they will want to keep everything to themselves because they do not want to be deprived again. I am not applauding this behaviour – I am only saying that it is something that should be expected.

There are many things that need to be considered. And one of them is that we fought for freedom without properly defining what it is. The circumstances that we were under made us believe that freedom meant walking around without a dompas, and dining in white people’s restaurants etc. We were desperate!

We now walk around without a dompas and we eat in white people’s restaurants. But are we free?

To be honest, to some extent I understand why people like Mogabe and Malema do what they do. They feel Africa’s pain, deeply. But we cannot fight fire with fire. History has taught us that.

You say black people need white people to teach them to care for the environment. Whose factories dump waste products into the ocean?

Don’t forget that while white people got ‘education’ black people got ‘Bantu education’. This was the colonialist’s plan to keep black people dependent on them. And my brother, you fell for it!

I agree that practices such as Ukuthwala are harmful and should not be accepted – but you seem to forget that all cultures (including white people’s culture) have practices that are rather harmful, but some things are not spoken about. I have spent many years amongst white people and I learnt that they do not make a habit of mocking themselves in the presence of black people. They know that they do not have to please us, and we need to know this too.

We could never erase what happened in the past, nor can we forget it. But we have cried for too long, and if we don’t stop, we may never heal!

It would be silly of us to destroy white suburbs and build huts. But we should be able to enjoy what was created on African soil because colonialism did not allow us to develop Africa our own way. Who knows what we would have come up with? I get the feeling it would have been beautiful and free of toxic chemicals!

We do not need physical change; we need a change in consciousness!

I think what our forefathers really wanted was a country where all people are respected and treated equally regardless of their race. A country where an architect values the ‘uneducated’ bricklayer and the bricklayer knows his value. We all know that they are both necessary to making the project a reality.

Sadly, in 2013, the bricklayer still thinks he is nothing without the architect – and the architect benefits from this. We need a country that encourages the bricklayer to constantly aim to improve himself. He should know his value, and not be satisfied with doing the same work for 20 years. It was not by chance that we were all given a brain!

As long as people like you keep saying things like these, white people will never respect black people, and black people will keep on believing that they are inferior. You might get a pat on the back from your white colleagues (who, by the way, see you as a black man on their leash) but your kind of thinking is not beneficial to our people.

Vuka mntakwethu!

This article was first published by Times Live. Please find the original article at http://www.timeslive.co.za/ilive/2013/04/23/black-people-don-t-need-white-people-ilive

Tendering Workshop for the Ginsberg Community

The Business Incubator, an initiative of the Steve Biko Centre, invites you to a Tendering Workshop in Ginsberg.

Facilitator: Lungile Sululu from the Steve Biko Foundation

Date: April 29, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, Eastern Cape

Cost: R20

For more information please contact Mr. Sululu on 043 642 1177 or email lungiles@sbf.org.za

Facilitator: Lungile Sululu from the Steve Biko Foundation

Date: April 29, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, Eastern Cape

Cost: R20

For more information please contact Mr. Sululu on 043 642 1177 or email lungiles@sbf.org.za

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

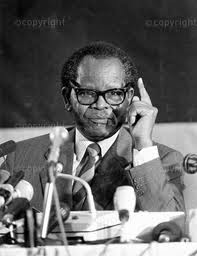

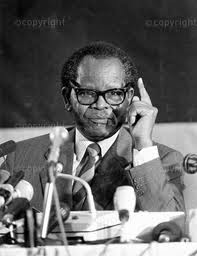

Tambo and The Fight for a Free South Africa

On 24 July 1951, Tambo qualified as an attorney. Mandela, by now also a qualified lawyer, had previously approached him to join in a partnership. They set up offices in Chancellor House, as Mandela and Tambo. As the firm became known, people travelled long distances, from around the country, to seek the services of the young law firm. When Mandela was banned in 1951, Tambo had to carry the workload on his own.

In 1953, Chief Albert Luthuli was elected President of the ANC and Tambo was appointed as National Secretary in place of Walter Sisulu, who had been banned by the government because of the Defiance Campaign. When the 1952 Defiance Campaign was called off, the ANC called a meeting of White activists. Tambo, Sisulu and Bram Fischer were the speakers at this meeting. Tambo carefully explained the aims of the Campaign and how Africans, Coloureds and Indians had responded to it. The audience was moved by his speech and shortly after this, the Congress of Democrats (COD) was formed, in 1953, with Fischer elected as chairperson.

When Canon Collins of St Pauls Church, London visited South Africa, in 1954, Father Huddleston and Tambo took him around to meet Sisulu and other ANC members. He spoke to Collins about his hopes of becoming an ordained minister of the church. This dream was not realised as Father Trevor Huddleston whom Tambo had come consider as his spiritual mentor was recalled to England in 1956.

At the 1954 ANC Congress, Tambo was elected Secretary General. That same year Tambo received his banning orders from the State. However, he remained actively involved in the background working as a member of the National Action Committee which drafted the Freedom Charter following extensive nationwide input and consultation. This was in the run up to the Congress of the People, (COP), convened in June 1955. When the COP was convened, Tambo could not attend due to the restrictions placed on him and had to observe the proceedings from a hiding place at Stanley Lollan’s residence in Kliptown, overlooking the square where the Congress was taking place.

During 1955 Tambo became engaged to Adelaide Tsukhudu, a nurse employed at Baragwanath Hospital. Their wedding was set for 22 December 1956, but it was nearly put off as Tambo was detained on treason charges on 5 December 1956. After all the accused were granted bail, the wedding took place as scheduled. After the preliminary hearings Tambo and Chief Albert Luthuli were acquitted. Altogether 155 members of the ANC were charged in what became known as the 1956 Treason Trial. In 1957, Duma Nokwe replaced Tambo as Secretary General of the ANC, while Tambo was elected Deputy President of the ANC. As early as April 1958 Tambo had confided in Adelaide that the ANC had wanted him together with the family to go into exile. By now the couple had three children, Thembi, Dali and Tselane.

During the ANC’s December 1958 conference the NEC appointed Tambo to chair the conference. A group of former ANC members, known as the Africanists, attempted to disrupt the meeting but Tambo was able to control the meeting leading them to eventually leave. The Africanists broke away from the ANC and in April 1959 constituted themselves as the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). More than a decade later, Tambo wrote a stinging criticism of the PAC, accusing them of being divisive and irresponsible.

In 1959, Tambo headed the ANC’s Constitutional Commission. The Tambo Commission recommended that more constitutional recognition be given to the ANC’S Women’s League (ANCWL) and the ANCYL, and endorsed non-racialism and the Freedom Charter, amongst other issues. The constitutional revision of the ANC came to be known as the Tambo Constitution. All the while he had to carry the burden of political work and the work of the law firm alone, since Mandela was still on trial.

In the meantime, Tambo began corresponding with a number of overseas sympathisers. Following the Sharpeville Massacre, Tambo embarked on a “Mission in Exile” in order to gain international support for the South African liberation movement. On 27 March 1960 Tambo was driven by Ronald Segal, the editor of the liberal journal, Africa South across the Bechuanaland (now Botswana) border. Whilst in Bechuanaland, telegrams that Tambo sent to the United Nations (UN) were intercepted and passed on to the South African authorities. Tambo’s stay in Bechuanaland became perilous and haunted by the constant fear of being abducted and returned to South Africa.

Yusuf Dadoo, the leader of the South African Communist Party (SACP) was also in Bechuanaland, having fled into exile. Frene Ginwala arranged travel documents and transport for Tambo, Dadoo and Segal from the Indian Consul in Kenya. The three men took off from Palapye, in a chartered plane to Tanganyika (now Tanzania). After spending a night in Nyasaland (Malawi), they landed in Dar es Salaam, Tanganiyika where they were met by Ginwala who took them to meet Julius Nyerere.

After that Tambo flew from Tanganyika to Nairobi, where he was issued with further travel documents by the Indian Government. The next day Tambo left for Tunisia where he was invited by the General Secretary of the World Assembly Youth, David Wirmark. It was here that he delivered his first speech outside the country. He also met President Habib Bourgiba of Tunis and was able to explain the ANC’s position to him. From here, he went to Ghana where he had an audience with Kwame Nkrumah and explained the situation in South Africa.

Tambo’s first visit to northern Europe was when he went to Denmark at the invitation of the Prime Minister on 1 May 1960. He addressed meetings in Copenhagen and Aarhus outlining the history of South Africa and called for trade unions to help the ANC’s boycott call. From here, he flew to London where he was met by his friends Father Huddleston and Canon Collins. In London, he had meetings with ANC exiles, Dadoo and representatives of the PAC. His intention was to try to bring together representatives of the liberation movements fighting the South African regime.

Thereafter, he flew to Egypt to enlist the support of the Egyptian leader, Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser. From here he flew to Ethiopia where he met with the Non-European United Front, a body made up of ANC and PAC exiles, that was set up to work together with a common purpose. Whilst in Ethiopia, he also addressed the first conference of African heads of state.

At the same time, arrangements were made for Adelaide and the children to travel to Swaziland and from there to Ghana and then on to London. A farmer from Swaziland, Oliver Tedley, transported them across the border into Swaziland. After six frustrating weeks, Adelaide and the children left for Botswana and from here, landed in Accra, Ghana three weeks later. A week later, on 15 September 1960, Adelaide and the children landed in London. Initially they stayed with James Philips a South African exile.

In the meantime Tambo had to go to New York to address the UN. The family then moved into a flat and Adelaide was able to find a job as a nurse at St George’s Hospital. There were times when she had to leave the children alone, locked up for the night, to work the night shift. In the years to come, Tambo saw very little of his family due to his hectic travelling and ANC commitments. Adelaide was forced to work between 12 and 20 hours per day to earn enough for the upkeep of the family. In addition, Adelaide opened her house to members of the ANC arriving in the United Kingdom. Tambo had little money and hardly spent his ANC allowance of £2 a week on himself, saving whatever he could for Christmas gifts and cards for his children.

In October 1962, a consultative meeting chaired by Govan Mbeki, was held in Lobatse, Botswana. It was to confirm the ANC’s NEC mandate, namely, that Tambo was to head the ANC’s diplomatic mission and to communicate to the world the situation in South Africa. As head of the ANC’s Mission in Exile, he had to oversee the growing number of ANC exiles, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) military camps, fundraising, the setting up ANC offices around the world, the welfare of ANC cadres were well taken care of and to interact with the international community. His use of consensus and the collective decision making helped tremendously.

When Chief Luthuli was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1961, Tambo accompanied Luthuli and his wife throughout their travels to Oslo. In January 1962 Tambo met Mandela and Joe Matthews in Dar es Salaam. Mandela explained to him the details of the decision to launch MK and armed operations, and the ANC’s need to cooperate closely with the SACP in this process. Mandela and Tambo then worked out a programme for the External Mission under the new circumstances whereby the latter had to develop diplomatic support for MK.

Mandela and Tambo travelled to a number of countries in North Africa. Together they returned to London where Mandela met with a number of important British officials and politicians. During this period Tambo also led an ANC delegation to the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in Ethiopia in May 1963. In July 1963, the bulk of the MK High Command were arrested. With the incarceration of the Rivonia trialists, it fell upon Tambo to take up leadership of MK.

In 1963, he visited the USSR and China, hoping to gain support from these two countries. The USSR made £ 300,000.00 available to Tambo in 1964. He was later to say that it did not mean that since the ANC was accepting assistance from the USSR that it was aligned to the Russians. At the same time, he had worked to win over Western countries in order to gain support from them. In 1964, Tambo arrived in Dar es Salaam to take up his post as head of MK and the ANC. He shared a guesthouse with other members of the ANC office.

During 1963 and 1964, Tambo made a number of high profile speeches to present the ANC to the world, the most prominent being one made to the UN in October 1963. This speech inspired the UN Resolution XVIII of 11 October 1963 calling on the South African Government to release all political prisoners. Tambo addressed the UN where his passionate plea for the release of political prisoners received a standing ovation. It was at the UN that Tambo met ES Reddy, an Indian national who was the Secretary of the Special Committee on Apartheid. The two men developed a long lasting, enduring friendship. Over the years Reddy became a useful ally of Tambo and the ANC. Support for the ANC’s cause abroad also came from the London Anti-Apartheid Movement. In 1964, Ronald Segal together with the London Anti-Apartheid Movement and Tambo’s involvement organised an International Conference on Economic Sanctions against South Africa.

Following the Rivonia Trial, Tambo called a consultative meeting of ANC representatives from around the world, in Lusaka on 8 January 1965 as it was becoming difficult to meet with the increasing number of branches being set up internationally. That same year he also negotiated with the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now African Union [AU]) and the Tanzanian Government for land to set up a military camp in Dar es Salaam. In 1965, he also set up another camp in newly independent Zambia.

At the same time, MK and Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) began to work together with the aim of infiltrating then Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In 1968, Tambo accompanied the MK group on a number of occasions when they went on reconnaissance expeditions along the Zambesi River, sleeping in the open with the group. Tambo named the group the Luthuli Detachment, in honour of Chief Luthuli who was killed in a tragic railway accident in July 1967 in Groutville, Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal). The Wankie Campaign was the first significant military campaign for the ANC. In spite of some victories against Rhodesian forces, the group was forced to retreat, as they had to face the military might of the combined South African and Rhodesian forces.

OR lived under constant pressure and stress, which at times affected his health and given the demands of his position he had little time to recuperate from illness. At the same time, there were strident criticisms from rank and file members over a host of issues ranging from military to social to political.

A memorandum from Chris Hani’s group that was incarcerated in Botswana following the

Wankie Campaign issued a scathing memorandum, upon their release, of various senior ANC leaders and accused Tambo of failing to adhere to democratic principles. Tambo was disturbed by the memorandum and at the low morale in the camps. As a result, he decided to call a consultative conference of the ANC. He sent word, secretly, to the leadership on Robben Island about the conference. After months of intense preparation, the conference of about 700 ANC members in exile, MK and the Congress Alliance partners took place on April 1969 at Morogoro, Tanzania. In his address to the conference, Tambo emphasised that it was a consultative conference.

At this meeting, Tambo tended his resignation from the ANC, following personal attacks. This threw the conference into disarray and Tambo was persuaded to return. A new executive was elected and Tambo was unanimously re-elected as President. This position was endorsed by the leadership on Robben Island in a message conveyed by Mac Maharaj following his release from the Island. The leadership was restructured into the Revolutionary Council, chaired by Tambo and included Yusuf Dadoo, Reg September and Joe Slovo. Tambo kept updated about discussions on the Island as he was briefed by prisoners who were released and through correspondence, via various sources that he had clandestinely developed, was able to communicate to the leadership on the Island.

In the aftermath of the 1976 student rebellion, Tambo had to rethink ways of effectively managing the organisation. He approached the Tanzanian Government for a piece of land to establish a school for exiles. The school was named after Solomon Mahlangu, an MK guerrilla who was executed by the Government after an attack on a warehouse on Goch Street, Johannesburg. He also recruited Pallo Jordan to develop Radio Freedom, on which Tambo often spoke, in Lusaka to broadcast ANC propaganda.

Tambo reached other organisations such as the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). However, the death of Steve Biko at the hands of the police in detention and the banning of other BCM activists meant that a planned meeting with the BCM leaders was set back. Tambo also met a number of visiting homeland leaders, in particular, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) in London. In 1978, Tambo headed a delegation to Vietnam where they attended numerous lectures and met with activists in the Vietnamese struggles. Subsequent to this visit, he commissioned a Politico-Military Strategy Council to lay the groundwork for mass support and mass mobilisation. The Commission recommended a programme whereby all opposition groups within the country would join forces around a broad programme of opposition to Apartheid.

Tambo was very mindful of the rights of women. He commissioned a Code of Conduct that saw that women’s rights are respected and upheld by all in the organisation. He tried to ensure that the abuse of women was eradicated.

Between 1983 and 1985, there were two mutinies in MK camps in Angola. Young cadres who wanted to be deployed back home mutinied when this did not take place. In addition deteriorating conditions at the camps also contributed to the mutiny. Tambo appointed James Stuart to head this Commission to investigate. It became known as the Stuart Commission. However, as early as 1983, Tambo visited camps, in Angola, to address cadres based there. Whenever he visited the camps, he would talk to the cadres about their problems. At times, he even entertained what one may consider trivial personal issues.

Following the signing of the Nkomati Accord between South Africa and Mozambique, cadres in the camps mutinied again, demanding to return home to fight. Again, Tambo addressed the cadres explaining to them the need for diplomacy under the circumstances, with the need to balance the undertaking of the armed struggle back home. As a result of growing frustrations of cadres in camps, in 1985, another ANC consultative conference took place in Kabwe, Zambia. Amongst many important issues that were dealt with and decisions that were arrived at, Tambo commissioned a Code of Conduct to deal with issues of procedure and detention. However despite the Code of Conduct, abuse in the camps did not stop.

Tambo remained acutely aware of the need to make and keep contact with both the civil and the corporate world. Already by the 1980s, he had met with American multinationals in order to explain the ANC’s position to them. Whilst Tambo was expanding the ANC’s network on a diplomatic, corporate, cultural and sporting level, the South African regime was becoming increasingly even more repressive at home and was engaging in more cross border raids.

On 8 January 1985, Tambo delivered his most dramatic speech calling on people to “Render South Africa Ungovernable.” Following the July 1985 State of Emergency, he appealed to all South Africans, Black and White, to make Apartheid unworkable and the country ungovernable. With social unrest increasing and the Apartheid Government under pressure, Tambo stated that this alone was insufficient and that alternative people’s structures had to be built.

That same year Tambo and the ANC met a high-powered delegation of the foremost captains of industry from South Africa. This meeting was due to the efforts of Gavin Relly, a director at Anglo American. At this meeting Tambo explained the ANC’s position and fielded questions from the understandably apprehensive business people. Subsequent to this meeting, the National African Confederation of Commerce, a Black business grouping, headed by Sam Motsunyana, also met with the ANC.

In October 1985, Tambo was asked to give evidence to the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Commons in London, where he had to field difficult questions and sometimes hostile questioners. The result of this was that the following year, the United Kingdom, as part of the Commonwealth, sent an Eminent Persons Group to investigate the situation in the country. Then in 1986, he called for a campaign to establish an alternative system of education and called for the unbanning of the Congress of South African Students (COSAS).

In 1987, Tambo appointed a high-powered Commission of ANC legal people to draw up a constitution to reflect the kind of country that the ANC wanted for the future. He also sat in on these meetings, often guiding the meetings. Tambo had consistently advocated support for a multiparty democracy and an entrenched Bill of Rights. Also in 1987, Tambo together with others conceived and headed a top-secret covert mission by MK known as Operation Vula. Tambo chose the operatives to infiltrate into the country to work underground establishing networks and arms caches.

In 1988, Tambo called an emergency meeting of the ANC’s Politico-Military Council (PMC) to determine the position of MK operations in South Africa. In spite of the South African Defence Force (SADF) massacring ANC members in Lesotho, Botswana and Mozambique, Tambo insisted that the ANC should maintain moral high ground and avoid the loss of civilian life in its operations. This was in response, especially, to when MK struck at two “soft targets,” fast food outlets in the country.

In 1988 Tambo appointed a President’s Team on Negotiations to draw up the ANC’s position and approach to the negotiations drawing from viewpoints from the exiles and the Mass Democratic Movement in the country. In the meantime, the South African establishment was secretly making moves to approach the ANC for negotiations through exploratory meetings. On 31 May 1989, Thabo Mbeki, after receiving the go ahead from Tambo called Professor Willie Esterhuyse, who had been part of these meetings, to set up a meeting between the ANC and the South African National Intelligence Service. Mbeki was in many ways a protégé of Tambo as the pair worked very closely together.

Following extensive discussions with the Front Line State leaders, Tambo led and worked closely with the ANC team which drafted the Harare Declaration. The declaration acknowledged that there may be an opportunity for negotiations with the South African regime with the end of Apartheid in mind. It explained the climate and principles, which had to be created, before negotiations could begin.

Pressure and exhaustion took its toll on Tambo and in 1989 he suffered a severe stroke that resulted in him losing his speech. Following his stroke, he was rushed from Lusaka to London on Tony Rowland’s executive plane on the order of President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, to Harley Street in London. Rowland also paid for the medical treatment. Against the advice of his physician and the NEC, Tambo continued his punishing work schedule and travelling on ANC business. He suffered another stroke in 1991 whilst undergoing medical treatment in Sweden. Again Rowland flew him back to London where he was treated.

With the unbanning of the ANC in 1990 and the process of transition already underway, the entire Tambo family flew back to South Africa in December 1990. However, Tambo was unable to address the welcoming crowd at the airport due to his loss of speech. A welcome rally was organised at Orlando Stadium, attended by a crowd of 70,000 people. At the ANC Conference, in Durban in 1991, Tambo declined to stand for any position. The position of National Chairman was created in his honour. Nelson Mandela was elected President of the organisation.

In 1991, Tambo was installed as Chancellor of the University of Fort Hare. In February 1993, he opened a large international conference in Johannesburg, chaired by Thabo Mbeki. Foreign dignitaries and representatives of anti-Apartheid movements filled the hall to listen to Tambo thank their countries and organisations for their contribution in helping to end Apartheid. Despite his illness, Tambo came to the ANC, in Johannesburg, office every day and still addressed public meetings of organisations.

During the early hours of the morning of 23 April 1993, Oliver Reginald Tambo passed away after a heart attack. He was honoured with a state funeral where scores of friends, supporters, colleagues and heads of state bade him farewell. His epitaph, reads, in his own words:

It is our responsibility to break down barriers of division and create a country where there will be neither Whites nor Blacks, just South Africans, free and united in diversity.

Position:

President (1967 - 1991) Deputy President (1958 - 1985) General Secretary (1955 - 1958)

References

• Callinicos L. (2004), Oliver Tambo. Beyond the Engeli Mountains, (David Philips Publishers), Claremont, Cape Town

• Jordan, P.Z. (2007). Oliver Tambo Remebered. Pan Macmillan, Johannesburg

• ANC (date unknown).Oliver Reginald Tambo. Available at www.anc.org.za online. Accessed on 17 October 2011

Biography retrieved from the South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/oliver-reginald-tambo

In 1953, Chief Albert Luthuli was elected President of the ANC and Tambo was appointed as National Secretary in place of Walter Sisulu, who had been banned by the government because of the Defiance Campaign. When the 1952 Defiance Campaign was called off, the ANC called a meeting of White activists. Tambo, Sisulu and Bram Fischer were the speakers at this meeting. Tambo carefully explained the aims of the Campaign and how Africans, Coloureds and Indians had responded to it. The audience was moved by his speech and shortly after this, the Congress of Democrats (COD) was formed, in 1953, with Fischer elected as chairperson.

When Canon Collins of St Pauls Church, London visited South Africa, in 1954, Father Huddleston and Tambo took him around to meet Sisulu and other ANC members. He spoke to Collins about his hopes of becoming an ordained minister of the church. This dream was not realised as Father Trevor Huddleston whom Tambo had come consider as his spiritual mentor was recalled to England in 1956.

At the 1954 ANC Congress, Tambo was elected Secretary General. That same year Tambo received his banning orders from the State. However, he remained actively involved in the background working as a member of the National Action Committee which drafted the Freedom Charter following extensive nationwide input and consultation. This was in the run up to the Congress of the People, (COP), convened in June 1955. When the COP was convened, Tambo could not attend due to the restrictions placed on him and had to observe the proceedings from a hiding place at Stanley Lollan’s residence in Kliptown, overlooking the square where the Congress was taking place.

During 1955 Tambo became engaged to Adelaide Tsukhudu, a nurse employed at Baragwanath Hospital. Their wedding was set for 22 December 1956, but it was nearly put off as Tambo was detained on treason charges on 5 December 1956. After all the accused were granted bail, the wedding took place as scheduled. After the preliminary hearings Tambo and Chief Albert Luthuli were acquitted. Altogether 155 members of the ANC were charged in what became known as the 1956 Treason Trial. In 1957, Duma Nokwe replaced Tambo as Secretary General of the ANC, while Tambo was elected Deputy President of the ANC. As early as April 1958 Tambo had confided in Adelaide that the ANC had wanted him together with the family to go into exile. By now the couple had three children, Thembi, Dali and Tselane.

During the ANC’s December 1958 conference the NEC appointed Tambo to chair the conference. A group of former ANC members, known as the Africanists, attempted to disrupt the meeting but Tambo was able to control the meeting leading them to eventually leave. The Africanists broke away from the ANC and in April 1959 constituted themselves as the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). More than a decade later, Tambo wrote a stinging criticism of the PAC, accusing them of being divisive and irresponsible.

In 1959, Tambo headed the ANC’s Constitutional Commission. The Tambo Commission recommended that more constitutional recognition be given to the ANC’S Women’s League (ANCWL) and the ANCYL, and endorsed non-racialism and the Freedom Charter, amongst other issues. The constitutional revision of the ANC came to be known as the Tambo Constitution. All the while he had to carry the burden of political work and the work of the law firm alone, since Mandela was still on trial.

In the meantime, Tambo began corresponding with a number of overseas sympathisers. Following the Sharpeville Massacre, Tambo embarked on a “Mission in Exile” in order to gain international support for the South African liberation movement. On 27 March 1960 Tambo was driven by Ronald Segal, the editor of the liberal journal, Africa South across the Bechuanaland (now Botswana) border. Whilst in Bechuanaland, telegrams that Tambo sent to the United Nations (UN) were intercepted and passed on to the South African authorities. Tambo’s stay in Bechuanaland became perilous and haunted by the constant fear of being abducted and returned to South Africa.

Yusuf Dadoo, the leader of the South African Communist Party (SACP) was also in Bechuanaland, having fled into exile. Frene Ginwala arranged travel documents and transport for Tambo, Dadoo and Segal from the Indian Consul in Kenya. The three men took off from Palapye, in a chartered plane to Tanganyika (now Tanzania). After spending a night in Nyasaland (Malawi), they landed in Dar es Salaam, Tanganiyika where they were met by Ginwala who took them to meet Julius Nyerere.

After that Tambo flew from Tanganyika to Nairobi, where he was issued with further travel documents by the Indian Government. The next day Tambo left for Tunisia where he was invited by the General Secretary of the World Assembly Youth, David Wirmark. It was here that he delivered his first speech outside the country. He also met President Habib Bourgiba of Tunis and was able to explain the ANC’s position to him. From here, he went to Ghana where he had an audience with Kwame Nkrumah and explained the situation in South Africa.

Tambo’s first visit to northern Europe was when he went to Denmark at the invitation of the Prime Minister on 1 May 1960. He addressed meetings in Copenhagen and Aarhus outlining the history of South Africa and called for trade unions to help the ANC’s boycott call. From here, he flew to London where he was met by his friends Father Huddleston and Canon Collins. In London, he had meetings with ANC exiles, Dadoo and representatives of the PAC. His intention was to try to bring together representatives of the liberation movements fighting the South African regime.

Thereafter, he flew to Egypt to enlist the support of the Egyptian leader, Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser. From here he flew to Ethiopia where he met with the Non-European United Front, a body made up of ANC and PAC exiles, that was set up to work together with a common purpose. Whilst in Ethiopia, he also addressed the first conference of African heads of state.

At the same time, arrangements were made for Adelaide and the children to travel to Swaziland and from there to Ghana and then on to London. A farmer from Swaziland, Oliver Tedley, transported them across the border into Swaziland. After six frustrating weeks, Adelaide and the children left for Botswana and from here, landed in Accra, Ghana three weeks later. A week later, on 15 September 1960, Adelaide and the children landed in London. Initially they stayed with James Philips a South African exile.

In the meantime Tambo had to go to New York to address the UN. The family then moved into a flat and Adelaide was able to find a job as a nurse at St George’s Hospital. There were times when she had to leave the children alone, locked up for the night, to work the night shift. In the years to come, Tambo saw very little of his family due to his hectic travelling and ANC commitments. Adelaide was forced to work between 12 and 20 hours per day to earn enough for the upkeep of the family. In addition, Adelaide opened her house to members of the ANC arriving in the United Kingdom. Tambo had little money and hardly spent his ANC allowance of £2 a week on himself, saving whatever he could for Christmas gifts and cards for his children.

In October 1962, a consultative meeting chaired by Govan Mbeki, was held in Lobatse, Botswana. It was to confirm the ANC’s NEC mandate, namely, that Tambo was to head the ANC’s diplomatic mission and to communicate to the world the situation in South Africa. As head of the ANC’s Mission in Exile, he had to oversee the growing number of ANC exiles, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) military camps, fundraising, the setting up ANC offices around the world, the welfare of ANC cadres were well taken care of and to interact with the international community. His use of consensus and the collective decision making helped tremendously.

When Chief Luthuli was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1961, Tambo accompanied Luthuli and his wife throughout their travels to Oslo. In January 1962 Tambo met Mandela and Joe Matthews in Dar es Salaam. Mandela explained to him the details of the decision to launch MK and armed operations, and the ANC’s need to cooperate closely with the SACP in this process. Mandela and Tambo then worked out a programme for the External Mission under the new circumstances whereby the latter had to develop diplomatic support for MK.

Mandela and Tambo travelled to a number of countries in North Africa. Together they returned to London where Mandela met with a number of important British officials and politicians. During this period Tambo also led an ANC delegation to the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in Ethiopia in May 1963. In July 1963, the bulk of the MK High Command were arrested. With the incarceration of the Rivonia trialists, it fell upon Tambo to take up leadership of MK.

In 1963, he visited the USSR and China, hoping to gain support from these two countries. The USSR made £ 300,000.00 available to Tambo in 1964. He was later to say that it did not mean that since the ANC was accepting assistance from the USSR that it was aligned to the Russians. At the same time, he had worked to win over Western countries in order to gain support from them. In 1964, Tambo arrived in Dar es Salaam to take up his post as head of MK and the ANC. He shared a guesthouse with other members of the ANC office.

During 1963 and 1964, Tambo made a number of high profile speeches to present the ANC to the world, the most prominent being one made to the UN in October 1963. This speech inspired the UN Resolution XVIII of 11 October 1963 calling on the South African Government to release all political prisoners. Tambo addressed the UN where his passionate plea for the release of political prisoners received a standing ovation. It was at the UN that Tambo met ES Reddy, an Indian national who was the Secretary of the Special Committee on Apartheid. The two men developed a long lasting, enduring friendship. Over the years Reddy became a useful ally of Tambo and the ANC. Support for the ANC’s cause abroad also came from the London Anti-Apartheid Movement. In 1964, Ronald Segal together with the London Anti-Apartheid Movement and Tambo’s involvement organised an International Conference on Economic Sanctions against South Africa.

Following the Rivonia Trial, Tambo called a consultative meeting of ANC representatives from around the world, in Lusaka on 8 January 1965 as it was becoming difficult to meet with the increasing number of branches being set up internationally. That same year he also negotiated with the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now African Union [AU]) and the Tanzanian Government for land to set up a military camp in Dar es Salaam. In 1965, he also set up another camp in newly independent Zambia.

At the same time, MK and Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) began to work together with the aim of infiltrating then Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In 1968, Tambo accompanied the MK group on a number of occasions when they went on reconnaissance expeditions along the Zambesi River, sleeping in the open with the group. Tambo named the group the Luthuli Detachment, in honour of Chief Luthuli who was killed in a tragic railway accident in July 1967 in Groutville, Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal). The Wankie Campaign was the first significant military campaign for the ANC. In spite of some victories against Rhodesian forces, the group was forced to retreat, as they had to face the military might of the combined South African and Rhodesian forces.

OR lived under constant pressure and stress, which at times affected his health and given the demands of his position he had little time to recuperate from illness. At the same time, there were strident criticisms from rank and file members over a host of issues ranging from military to social to political.

A memorandum from Chris Hani’s group that was incarcerated in Botswana following the

Wankie Campaign issued a scathing memorandum, upon their release, of various senior ANC leaders and accused Tambo of failing to adhere to democratic principles. Tambo was disturbed by the memorandum and at the low morale in the camps. As a result, he decided to call a consultative conference of the ANC. He sent word, secretly, to the leadership on Robben Island about the conference. After months of intense preparation, the conference of about 700 ANC members in exile, MK and the Congress Alliance partners took place on April 1969 at Morogoro, Tanzania. In his address to the conference, Tambo emphasised that it was a consultative conference.

At this meeting, Tambo tended his resignation from the ANC, following personal attacks. This threw the conference into disarray and Tambo was persuaded to return. A new executive was elected and Tambo was unanimously re-elected as President. This position was endorsed by the leadership on Robben Island in a message conveyed by Mac Maharaj following his release from the Island. The leadership was restructured into the Revolutionary Council, chaired by Tambo and included Yusuf Dadoo, Reg September and Joe Slovo. Tambo kept updated about discussions on the Island as he was briefed by prisoners who were released and through correspondence, via various sources that he had clandestinely developed, was able to communicate to the leadership on the Island.

In the aftermath of the 1976 student rebellion, Tambo had to rethink ways of effectively managing the organisation. He approached the Tanzanian Government for a piece of land to establish a school for exiles. The school was named after Solomon Mahlangu, an MK guerrilla who was executed by the Government after an attack on a warehouse on Goch Street, Johannesburg. He also recruited Pallo Jordan to develop Radio Freedom, on which Tambo often spoke, in Lusaka to broadcast ANC propaganda.

Tambo reached other organisations such as the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). However, the death of Steve Biko at the hands of the police in detention and the banning of other BCM activists meant that a planned meeting with the BCM leaders was set back. Tambo also met a number of visiting homeland leaders, in particular, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) in London. In 1978, Tambo headed a delegation to Vietnam where they attended numerous lectures and met with activists in the Vietnamese struggles. Subsequent to this visit, he commissioned a Politico-Military Strategy Council to lay the groundwork for mass support and mass mobilisation. The Commission recommended a programme whereby all opposition groups within the country would join forces around a broad programme of opposition to Apartheid.

Tambo was very mindful of the rights of women. He commissioned a Code of Conduct that saw that women’s rights are respected and upheld by all in the organisation. He tried to ensure that the abuse of women was eradicated.

Between 1983 and 1985, there were two mutinies in MK camps in Angola. Young cadres who wanted to be deployed back home mutinied when this did not take place. In addition deteriorating conditions at the camps also contributed to the mutiny. Tambo appointed James Stuart to head this Commission to investigate. It became known as the Stuart Commission. However, as early as 1983, Tambo visited camps, in Angola, to address cadres based there. Whenever he visited the camps, he would talk to the cadres about their problems. At times, he even entertained what one may consider trivial personal issues.

Following the signing of the Nkomati Accord between South Africa and Mozambique, cadres in the camps mutinied again, demanding to return home to fight. Again, Tambo addressed the cadres explaining to them the need for diplomacy under the circumstances, with the need to balance the undertaking of the armed struggle back home. As a result of growing frustrations of cadres in camps, in 1985, another ANC consultative conference took place in Kabwe, Zambia. Amongst many important issues that were dealt with and decisions that were arrived at, Tambo commissioned a Code of Conduct to deal with issues of procedure and detention. However despite the Code of Conduct, abuse in the camps did not stop.

Tambo remained acutely aware of the need to make and keep contact with both the civil and the corporate world. Already by the 1980s, he had met with American multinationals in order to explain the ANC’s position to them. Whilst Tambo was expanding the ANC’s network on a diplomatic, corporate, cultural and sporting level, the South African regime was becoming increasingly even more repressive at home and was engaging in more cross border raids.

On 8 January 1985, Tambo delivered his most dramatic speech calling on people to “Render South Africa Ungovernable.” Following the July 1985 State of Emergency, he appealed to all South Africans, Black and White, to make Apartheid unworkable and the country ungovernable. With social unrest increasing and the Apartheid Government under pressure, Tambo stated that this alone was insufficient and that alternative people’s structures had to be built.

That same year Tambo and the ANC met a high-powered delegation of the foremost captains of industry from South Africa. This meeting was due to the efforts of Gavin Relly, a director at Anglo American. At this meeting Tambo explained the ANC’s position and fielded questions from the understandably apprehensive business people. Subsequent to this meeting, the National African Confederation of Commerce, a Black business grouping, headed by Sam Motsunyana, also met with the ANC.

In October 1985, Tambo was asked to give evidence to the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Commons in London, where he had to field difficult questions and sometimes hostile questioners. The result of this was that the following year, the United Kingdom, as part of the Commonwealth, sent an Eminent Persons Group to investigate the situation in the country. Then in 1986, he called for a campaign to establish an alternative system of education and called for the unbanning of the Congress of South African Students (COSAS).

In 1987, Tambo appointed a high-powered Commission of ANC legal people to draw up a constitution to reflect the kind of country that the ANC wanted for the future. He also sat in on these meetings, often guiding the meetings. Tambo had consistently advocated support for a multiparty democracy and an entrenched Bill of Rights. Also in 1987, Tambo together with others conceived and headed a top-secret covert mission by MK known as Operation Vula. Tambo chose the operatives to infiltrate into the country to work underground establishing networks and arms caches.

In 1988, Tambo called an emergency meeting of the ANC’s Politico-Military Council (PMC) to determine the position of MK operations in South Africa. In spite of the South African Defence Force (SADF) massacring ANC members in Lesotho, Botswana and Mozambique, Tambo insisted that the ANC should maintain moral high ground and avoid the loss of civilian life in its operations. This was in response, especially, to when MK struck at two “soft targets,” fast food outlets in the country.

In 1988 Tambo appointed a President’s Team on Negotiations to draw up the ANC’s position and approach to the negotiations drawing from viewpoints from the exiles and the Mass Democratic Movement in the country. In the meantime, the South African establishment was secretly making moves to approach the ANC for negotiations through exploratory meetings. On 31 May 1989, Thabo Mbeki, after receiving the go ahead from Tambo called Professor Willie Esterhuyse, who had been part of these meetings, to set up a meeting between the ANC and the South African National Intelligence Service. Mbeki was in many ways a protégé of Tambo as the pair worked very closely together.

Following extensive discussions with the Front Line State leaders, Tambo led and worked closely with the ANC team which drafted the Harare Declaration. The declaration acknowledged that there may be an opportunity for negotiations with the South African regime with the end of Apartheid in mind. It explained the climate and principles, which had to be created, before negotiations could begin.

Pressure and exhaustion took its toll on Tambo and in 1989 he suffered a severe stroke that resulted in him losing his speech. Following his stroke, he was rushed from Lusaka to London on Tony Rowland’s executive plane on the order of President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, to Harley Street in London. Rowland also paid for the medical treatment. Against the advice of his physician and the NEC, Tambo continued his punishing work schedule and travelling on ANC business. He suffered another stroke in 1991 whilst undergoing medical treatment in Sweden. Again Rowland flew him back to London where he was treated.

With the unbanning of the ANC in 1990 and the process of transition already underway, the entire Tambo family flew back to South Africa in December 1990. However, Tambo was unable to address the welcoming crowd at the airport due to his loss of speech. A welcome rally was organised at Orlando Stadium, attended by a crowd of 70,000 people. At the ANC Conference, in Durban in 1991, Tambo declined to stand for any position. The position of National Chairman was created in his honour. Nelson Mandela was elected President of the organisation.

In 1991, Tambo was installed as Chancellor of the University of Fort Hare. In February 1993, he opened a large international conference in Johannesburg, chaired by Thabo Mbeki. Foreign dignitaries and representatives of anti-Apartheid movements filled the hall to listen to Tambo thank their countries and organisations for their contribution in helping to end Apartheid. Despite his illness, Tambo came to the ANC, in Johannesburg, office every day and still addressed public meetings of organisations.

During the early hours of the morning of 23 April 1993, Oliver Reginald Tambo passed away after a heart attack. He was honoured with a state funeral where scores of friends, supporters, colleagues and heads of state bade him farewell. His epitaph, reads, in his own words:

It is our responsibility to break down barriers of division and create a country where there will be neither Whites nor Blacks, just South Africans, free and united in diversity.

Position:

President (1967 - 1991) Deputy President (1958 - 1985) General Secretary (1955 - 1958)

References

• Callinicos L. (2004), Oliver Tambo. Beyond the Engeli Mountains, (David Philips Publishers), Claremont, Cape Town

• Jordan, P.Z. (2007). Oliver Tambo Remebered. Pan Macmillan, Johannesburg

• ANC (date unknown).Oliver Reginald Tambo. Available at www.anc.org.za online. Accessed on 17 October 2011

Biography retrieved from the South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/oliver-reginald-tambo

Biography of the Week: Oliver Tambo

Names: Tambo, Oliver Reginald

Born: 27 October 1917, Nkantolo, Bizana, Mpondoland, Eastern Cape, South Africa

Died: 24 April 1993, Johannesburg

In summary: Teacher, lawyer, President and National Chairperson of the ANC.

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (OR) was born in the village of Kantilla, Bizana, in the Mpondoland (eQawukeni), region of the Eastern Cape, on 27 October 1917. His mother, Julia, was the third wife of Mzimeni Tambo, son of a farmer and an assistant salesperson at a local trading store. His father had four wives and ten children and, although illiterate, lived comfortably. Mzimeni Tambo was a traditionalist, but also saw the importance of Western education. Later, Mzimeni converted to Christianity while Oliver's mother was already a devout Christian. After his birth, Oliver was christened Kaizana, after Kaizer Wilhelm of Germany, whose forces fought the British during World War 1. This was his father's way of showing his political awareness and his opposition to the British colonisation of Pondoland in 1878.

As a young boy, he was given the task of herding his father’s cattle. With his fellow herders, he soon learnt to hunt birds, take part in stick fighting (at which he was quite adept) and model animals from clay.

When Tambo was six his father informed him that he was to start school, which was about a kilometre from his home. After enrolling, his teacher informed him that he had to have a "school name" and therefore his father gave him the name Oliver. Tambo passed Sub A, after which he attended another school at Embhobeni. Here he was first introduced to formal music, which became a lifelong activity and hobby.

His father, intent on providing his children with a good education, moved his children to the Ludeke Methodist School, some 16 kilometres away from the homestead. Occasionally his father would lend Tambo his horse to travel to school. To overcome the inconvenience of travelling the long distance to school his father got him to board with three families, all of whom who lived near the school.

In April 1928, Tambo and his brother Alan enrolled at the Anglican Holy Cross missionary school at Flagstaff in the Eastern Cape. His father could not afford their fees, but through two English women who were total strangers to them, Joyce and Ruth Goddard, assisted by sending a sum of £10 every year to cover his educational costs. In addition, one of his older brothers who worked as a migrant labourer in Natal, (now KwaZulu-Natal) also sent part of his wages to cover any additional costs. Tambo’s spiritual life was nurtured at Holy Cross where he was baptised as a Christian into the Anglican fold.

At this school, Tambo became a good cricketer and soccer player, and acquired quite a reputation as an athlete. He also established his prowess as a stick fighter. Amongst the schoolchildren at this school, was Fikile Bam, who was later imprisoned on Robben Island for Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM) activities and rose to become a prominent attorney.

Tambo excelled at his studies but due to a lack of funds he was forced to repeat Standard Six (Grade Eight) two times in spite of passing at his first attempt. In 1934 he set out for St Peter's Secondary School in Rosettenville, Johannesburg with the assistance of Miss Tidmarsh his former teacher.

Apart from participating in soccer, tennis and cricket at St Peter’s, he was also a member of the school’s choir. At the age of 16, while on holiday in Kantolo, Tambo and some friends formed the Bizana Students Association (BSA). He was elected as Secretary of the organisation and Caledon Mda, was elected Chairperson. The aim of the BSA was to mobilise students during the holidays and engage them in organised activities.

Tambo was offered the position of Head Prefect at school but declined in favour of another student. Instead, he took up the position of Deputy Head Prefect. At about this time he renounced alcohol, vowing never to consume any more, something he did throughout his life. Tragedy struck during this period as his parents passed away within a year of each other.

In November 1936, he wrote his Junior Certificate (JC) examination, alongside black and white students in the Transvaal (now Gauteng). For the first time in history, two African students, one being Tambo, passed the JC examination with a first class. The Transkei Bhunga (Assembly of Chiefs), awarded him a five-year scholarship of £30 per annum. The University of South Africa also awarded him a two-year scholarship of £20. He then sat for the matriculation examinations in December 1938, which he passed with a first class pass.

Tambo initially wanted to study medicine, but at the time, no tertiary medical school accepted Black students in that field. He opted to study the sciences at the University of Fort Hare. At university, he first met Nelson Mandela, where both were members of the Students Christian Association. From his first year, Tambo taught Sunday school. He was also part of a singing group of eight students that was broadcast over the local radio station in Grahamstown. At the same time, he was stricken with asthma, a condition that he endured throughout his life.

In 1941, a White person in charge of the university kitchen assaulted Black women working there. An enquiry into the issue exonerated the man involved. The students convened a meeting and following intense debate, influenced by Tambo’s guidance, went on a boycott. In 1942, he was unanimously elected as Chairperson of the Students' Committee of his residence, Beda Hall. After three years, Tambo graduated with a B.Sc. degree in mathematics and physics from the University College of Fort Hare. He then enrolled for a diploma in higher education.

During this period Tambo led an initiative for students to rebuild a disused tennis court on the campus in order to pass time on Sundays. When the tennis court was completed, the students scheduled an opening ceremony, which Tambo reported to the Warden. The authorities declined permission for the students to play tennis on Sundays, as they believed it was a breach of the faith. The students then embarked on a policy of non-cooperation with the university authorities. As a consequence, Tambo, who at the time was Secretary of the Students Representative Council, together 45 other students, was expelled. All but 10 of them were readmitted after two or three weeks.

After his expulsion, Tambo went back to his home in Kantolo. He then applied for teaching jobs but was turned down when prospective employers learnt that he was expelled from University. Fortunately, he was offered a position as a teacher in Physics and Mathematics at his alma mater, St Peter's, where he spent five years. Former students taught by him recall his engaging style of teaching and consider him as an outstanding teacher. During this period Tambo became part of a small network of the young African elite in Johannesburg.

In 1942, he met Walter Sisulu, an estate agent whose office was used as a regular gathering place by young intellectuals. It was here that he also met other likeminded young people like Anton Lembede, Jordan Ngubane and Nelson Mandela, a fellow student from Fort Hare. Sisulu invited Tambo to his house where he was soon a regular guest on weekends.

Tambo, Sisulu, Mandela and other young intellectuals of the time regularly visited the house of Dr AB Xuma, a medical doctor who was also the President of the African National Congress (ANC). Here they formulated a plan to revive the ANC and make it more accessible to ordinary people. Tambo became informally involved in discussions of a committee of ANC members and Xuma responsible for drawing up a document called the African Claims in South Africa. He continued to do so until the final stages of its preparations. The ANC adopted this document at its 1943 Bloemfontein conference.

The idea of a national grouping of young men was conceived by Tambo and this idea crystallised into the beginnings of the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL). In December 1943, the ANCYL was formally accepted by the ANC at its Congress in Botshabelo, Bloemfontein and in September 1944, it held its official inauguration. Speakers at this meeting included Dr Xuma, Selope Thema, Dan Tloome and Tambo. Anton Lembede was elected President of the new ANCYL, AP Mda as the Vice President, Tambo as the Secretary and Sisulu as its Treasurer.

In 1948, the National Party (NP) came into power and a number of discriminatory laws were put into place. At around this time, Tambo enrolled to study law through correspondence. With the NP Government, passing more stringent laws against the disenfranchised population, the ANCYL, with Tambo as the scribe, prepared a Programme of Action, selecting tactics employed by other organisations in other campaigns – the civil disobedience campaign of the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign of the Indian organisations, strikes by the labour movement, mass action by the Communist Party of South Africa as well as grass roots campaigns such as that of James Mpanza’s Sofasonke movement.

At the 1948, ANC conference the ANCYL presented its document. However, Dr Xuma was not in favour of confrontational politics. The ANCYL resolved not to support his re-election as president unless he endorsed the Programme of Action. The conference itself accepted the Programme of Action but Xuma rejected the principle of the boycott tactics suggested by members of the ANCYL. Tambo and Ntsu Mokgehle (later to become the Prime Minister of Lesotho) then went and convinced Dr James S Moroka to stand as the ANC’s President. He was duly elected and the conference formally adopted the Programme of Action.

By 1948, Tambo was serving his law articles with a company of White lawyers, Max Kramer and Tuch. At the end of 1949, Tuch and Tambo joined the company of Solomon Kowalsky. One of his first cases at this company was a dispute among the Bafokeng people over land rights in Rustenburg, Western Transvaal (now North West Province). His sound knowledge of customary law helped, successfully, to conclude the case. At the same time he enrolled and studied by correspondence through the University of South Africa, studying by candle light at home.

Read the full biography from the South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/oliver-reginald-tambo

The First Crucial Steps to Starting and Running a Business

The Business Incubator, an initiative of the Steve Biko Centre, invites you to a workshop on the first crucial steps to starting and running a business.

Facilitator: Lungile Sululu from the Steve Biko Foundation

Date: April 25, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, Eastern Cape

Cost: R20

Facilitator: Lungile Sululu from the Steve Biko Foundation

Date: April 25, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, Eastern Cape

Cost: R20

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

The Poor Black Masses Need Black Consciousness Now More Than Ever

By Nompumelelo Zinhle Manzini

In the Quest for a True Humanity, I Write What I Like Steve Biko wrote that “Black Consciousness is an attitude of the mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time, its essence is the realisation by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their oppression- the blackness of the skin- and to operate as a group to rid themselves of the shackles that blind them to perpetual servitude”

I attended the fourth session of the FrankTalk Dialogues. These dialogues are intended for us as the youth to engage in discussions on prominent issues that impact our contemporary South African society ranging from political, to economic and social development. The key topic that we discussed together with the panellists and the live audience was Biko and Black Consciousness, Today. Mr Pandelani Nefelovhodwe, a panellist and former BCM leader, stated that “the apartheid economy is still intact” and that on its own suggests for me that the Black Consciousness is still greatly needed and relevant. The sad reality is that the movement is slowly dying out, whereas this is the time when it should be at its peak.

If the apartheid economy is still intact as Mr Nefelovhodwe suggested, this means that a large number of our people are repressed. Thus their “self” is inexistent and one of the key issues that Black Consciousness teaches is for people to have “a ‘self’ and to further find their identity. Therefore how can we as a nation progress effectively if there are still people who are repressed by the government that was meant to liberate them? Our people’s repression is a result of many issues such as the poor leadership that we have in our government, which has a trickle-down effect on our economic, social and somewhat political freedom. Instead of black men rallying together with their fellow brothers around the cause of their oppression which is “the blackness of [their] skin” and the dismal services it entitles one to, i.e. poor education system creates even greater divisions amongst blacks.

I for one feel that the reason that the BCM is dying out is because it’s only amongst the educated black elite in our society. For instance, most of the live audience members at these dialogues are young people who are largely informed and somewhat educated. The room gets full of conscious individuals and these are the people who don’t need to hear about BCM. It’s our fellow brothers and sisters who are somewhere in Alexander who don’t want to challenge the system that need to hear about BCM. Another possible reason why BC is fading away is because our generation engages in many dialogues but we don’t see much action! As Mr Nefolovhodwe said on Tuesday night as “the youth [we need] to organise [ourselves]” and use the many advanced resources that we have to awaken our people to consciousness”.

In the Quest for a True Humanity, I Write What I Like Steve Biko wrote that “Black Consciousness is an attitude of the mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time, its essence is the realisation by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their oppression- the blackness of the skin- and to operate as a group to rid themselves of the shackles that blind them to perpetual servitude”

I attended the fourth session of the FrankTalk Dialogues. These dialogues are intended for us as the youth to engage in discussions on prominent issues that impact our contemporary South African society ranging from political, to economic and social development. The key topic that we discussed together with the panellists and the live audience was Biko and Black Consciousness, Today. Mr Pandelani Nefelovhodwe, a panellist and former BCM leader, stated that “the apartheid economy is still intact” and that on its own suggests for me that the Black Consciousness is still greatly needed and relevant. The sad reality is that the movement is slowly dying out, whereas this is the time when it should be at its peak.

If the apartheid economy is still intact as Mr Nefelovhodwe suggested, this means that a large number of our people are repressed. Thus their “self” is inexistent and one of the key issues that Black Consciousness teaches is for people to have “a ‘self’ and to further find their identity. Therefore how can we as a nation progress effectively if there are still people who are repressed by the government that was meant to liberate them? Our people’s repression is a result of many issues such as the poor leadership that we have in our government, which has a trickle-down effect on our economic, social and somewhat political freedom. Instead of black men rallying together with their fellow brothers around the cause of their oppression which is “the blackness of [their] skin” and the dismal services it entitles one to, i.e. poor education system creates even greater divisions amongst blacks.

I for one feel that the reason that the BCM is dying out is because it’s only amongst the educated black elite in our society. For instance, most of the live audience members at these dialogues are young people who are largely informed and somewhat educated. The room gets full of conscious individuals and these are the people who don’t need to hear about BCM. It’s our fellow brothers and sisters who are somewhere in Alexander who don’t want to challenge the system that need to hear about BCM. Another possible reason why BC is fading away is because our generation engages in many dialogues but we don’t see much action! As Mr Nefolovhodwe said on Tuesday night as “the youth [we need] to organise [ourselves]” and use the many advanced resources that we have to awaken our people to consciousness”.

FNB Business Banking Workshop

The Business Incubator, an initiative of the Steve Biko Centre, invites you to a workshop on FNB Business Banking to be held in Ginsberg.

Facilitator: Representative from FNB

Date: April 24, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, King William's Town, Eastern Cape

Cost: Free

NB: Clients are urged to book in advance for the Micro MBA Workshop.

Facilitator: Representative from FNB

Date: April 24, 2013

Time: 10:00 – 12:00

Venue: The Steve Biko Centre, One Zotshie Street, Ginsberg, King William's Town, Eastern Cape

Cost: Free

NB: Clients are urged to book in advance for the Micro MBA Workshop.

Monday, April 22, 2013

Police “Shoot to Kill” in Post-Apartheid South Africa

By Tshepo Ntokoane, Founder of the Andries Tatane Foundation

Bloemfontein, Free State Province, South Africa

During the apartheid regime, we firmly condemned the naked police brutality of the Sharpeville Massacre, the Langa Massacre and many other incidents of this nature. Today, decades after ‘freedom’, we give ourselves a round of applause and congratulate the inhuman acts of brutality by police. Cases such as the Marikana “Massacre” are referred to as “responsible policing.”

What happened to ubuntu? What happened to batho pele (people first)? Is it the truth or what we can prove in court that matters now? Where have we placed our people’s dignity in the rankings? Last?

The late Prof. Chinua Achebe once said “We cannot trample upon the humanity of others without devaluing our own.” Where do recent patterns of police brutality place us in as far as ubuntu or humanity is concerned?

No one deserves to die like Tatane, Mido and the miners of Marikana. We all have the right of dignity.

Reducing police training from 2 years to 1 year; hiring anybody, even those with no passion to protect our communities because we want to create employment; employing (in senior positions) individuals without experience in policing is the reason South Africa is faced with this crisis today. It puzzles me that government refuses to set up a commission of inquiry into police conduct even though stats show 1 722 cases and 720 deaths related to police brutality reported to the IPID in 2011/2012.

The ideology behind the police actions in this country remains “shoot to kill” in a democratic country; similar to "skop, skiet en donder" during the Aparthied regime.