REMEMBERING ROBERT MANGALISO SOBUKWE:

THE REVOLUTIONARY THINKER

By Jaki Seroke

Ma Veronica Sobukwe captured the essence of her

late husband’s core mission in life when she chose the apt inscription for his

gravestone: “True leadership demands complete subjugation of self, absolute

honesty, integrity and uprightness of character, courage and fearlessness, and

above all, a consuming love for one’s people.”

Using a political lens, the kernel of Robert

Mangaliso Sobukwe’s contribution to public discourse in South Africa may best

be understood as revolutionary thought leadership.

He noted early on, that in African history some

chiefs and traditional leaders had, of their own free will, participated in the

sale of their subjects to slave traders. They had showed no care for the

well-being of their own people, and gleefully focused on self-enrichment. They collaborated

with foreign invaders to entrap African people and turn them into beasts of

burden. They were invariably used as pacifiers to help get little or no

resistance. This anomaly could replicate itself in the modern age if trusting

Africans were not consciously aware of their history.

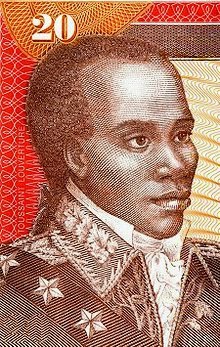

In the Americas, for instance, the indigenous

people fought vigorously against the white man’s slavery system. Once captured,

they preferred to commit suicide rather than live as slaves. The slave traders

then went across the Atlantic sea to fetch cowed products. Sobukwe extolled the

revolutionary deeds of Toussaint L’Overture, who led the San Domingo (Haiti)

slave rebellion to victory.

In the Americas, for instance, the indigenous

people fought vigorously against the white man’s slavery system. Once captured,

they preferred to commit suicide rather than live as slaves. The slave traders

then went across the Atlantic sea to fetch cowed products. Sobukwe extolled the

revolutionary deeds of Toussaint L’Overture, who led the San Domingo (Haiti)

slave rebellion to victory.

A SCHOLAR AND A

FREEDOM FIGHTER

Sobukwe developed into a formidable intellectual

and acquired academic honours in the languages, economics, law and political

science.

His outstanding leadership of the liberation

movement was infused with revolutionary ideas which marked a radical departure

from conformity, compromise and careless submission to the whims of the powers

that be. He acknowledged the influence of intellectuals from the All Africa

Convention (AAC) in his initial development. The AAC was marginalised from the

mainstream of public discussions due to their non-conformist approach. Sobukwe

took the popular platform in the schools, tertiary institutions and the press

and tamed it.

His Completers’ Speech at the University of Fort

Hare was a game changer in student politics – influencing southern Africa’s

burgeoning intellectuals. The historical impact of his speech can only be

regarded as a forerunner to Onkgopotse Abram Tiro’s graduation address at

Turfloop University in 1972.

Mainstream thought leaders like ZK Matthews,

Chief Albert Luthuli and their protégés, Nelson Mandela and OR Tambo,

subscribed to the concept of “exceptional-ism” for South Africa. In their

prognosis, the country’s colonialism was complex and of a special kind – after

the Act of Union of 1909 – and could not be easily likened to the rest of the

African continent. They believed that a national convention by all the race

groups was best placed to chart a peaceful settlement suitable to all.

The old guard leadership were influenced by

Booker T Washington’s Up from Slavery, which advocated moderation and gradualism

in winning changes from the authorities. They vouched for steady reforms, the

buildup of an African bourgeoisie and cooperation of the racial groups under

multi-racialism.

Sobukwe on the other hand read the works of WEB

Du Bois, George Padmore and other militant revolutionaries in the worldwide Pan

African movement. He stated that national politics in South Africa could only

be understood from an international perspective.

REVOLUTIONARY THOUGHT

LEADER

As a thought leader, Sobukwe interpreted

abstract concepts of political theory into concrete ideas which could be

understood by ordinary folk. His entire writings do not carry a single

exclamation mark. There is no anger and rancour in the way in which he

expresses strongly-held ideas against land dispossession, exploitation and

racial bigotry. He consciously exercised intellectual rigour and discipline.

Under his watch, the PAC’s eco-system blended

various intellectual disciplines – including those who were seemingly in

opposition and contradiction to each other – to work seamlessly together in a

united front, under the banner of African Nationalism. The church, business,

youth, students, rural farmers and traditional communities, the proletariat,

and professionals found space to air their views and be heard. He linked the

PAC with the 1949 Programme of Action – which he drafted. The PAC was also part

of the continent-wide winds of change.

The national executive committee of the Pan

Africanist Congress was referred to in the newspapers as Sobukwe’s cabinet

ministry, acting as a shadow government to the ruling settler regime. It had

luminaries like Nkutsuoe Peter Raboroko, a premier political theorist; Lekoane

Zephania Mothopeng, a leading educationist who campaigned against the Bantu

Education bills; PK Leballo, a second world war veteran; Jacob Nyaose, labour

federation unionist; and a host of other rising revolutionary intellectuals.

Founder of the congress youth league, AP Mda, served in the backroom as a

spiritual leader.

The policies of the PAC were Africanist in

orientation, original in conception, creative in purpose, socialist in content,

democratic in form, and non-racial in approach. They recognized the primacy of

the material, spiritual and intellectual interests of the individual. They

guaranteed human rights and basic freedoms to the individual – not minority

group rights, which would transport apartheid into a free world.

His comrades fondly referred to Sobukwe as ‘the

Prof’ – a term of endearment for his charismatic leadership and recognition of

his intellectual prowess. They were however all required to return to the

source – the masses – and show the light, in biblical simplicity. They formed

unity between workers, poor peasants, and revolutionary intellectuals. Robert

Sobukwe’s team went on to set the pace for the national liberation struggle

from 1960 onwards by putting South Africa (Azania) as a troubled spot on the

world map.

His comrades fondly referred to Sobukwe as ‘the

Prof’ – a term of endearment for his charismatic leadership and recognition of

his intellectual prowess. They were however all required to return to the

source – the masses – and show the light, in biblical simplicity. They formed

unity between workers, poor peasants, and revolutionary intellectuals. Robert

Sobukwe’s team went on to set the pace for the national liberation struggle

from 1960 onwards by putting South Africa (Azania) as a troubled spot on the

world map.

Sobukwe’s abiding concern has been that Africa

as a unified whole could participate as an equal in world affairs. The

patchwork of colonial borders drafted at the 1884 Berlin Conference had to be

ultimately done away with. A united Africa, under a single government, could

spread its humanising influence to resolve conflicts among nations – after the

League of Nations had dismally failed to contain and control Nazi Germany’s

aggression – and to having its civilisation appreciated and understood.

Sobukwe’s own lifestyle was an expression of his

ideas on mass-based leadership. He adopted the political standpoint of ordinary

folks in the rural areas and in the urban cities. He led a humble life, and

could relate to the poor and ‘the unwashed’, engaging them in genuine dialogue

on matters of national importance, even though he had held a ‘prestigious

position’ as a senior tutor of languages at Witwatersrand University. He knew

that positions like his, shorn of the frills and trappings, were dominated by

right-wingers, liberals and leftists from minority groupings “who arrogantly

appropriate to themselves the right to plan and think for the Africans.” If he

conformed to the status quo, he would be domesticated with a dog-collar mark as

in the fable of the Jackal and the Dog.

Sobukwe loved and glorified God. He believed in

the power of prayer and called his family and comrades to do likewise. He

became a lay preacher in the Methodist church. The PAC followed his path –

initiated by the slogan first coined by AP Mda – of making Christianity and

other religious beliefs relevant to the continent by stating that “African is

for Africans, Africans for Humanity, and Humanity for God.”

POLITICAL OPPONENTS

AND RIVALS

After the Sharpeville and Langa massacres,

Sobukwe was singled out for severe punishment by the National Party

administration. He was imprisoned for three years in hard labour. The

whites-only parliament extended his imprisonment by enacting the Sobukwe Clause

to keep him in solitary confinement without trial for six more years. They fed

him pieces of broken glass in his food, poisoned him in secret, and when he

developed traces of lung cancer they banished him to Galeshewe township in

Kimberley. He died a banned person in February 1978.

He served the African people selflessly. He

suffered under the yoke of oppressive laws like the majority of the people.

More than anything else, Mangaliso Sobukwe sacrificed himself and his family

for the national liberation of African people.

His detractors who supported the Bantustan

system paired him with Stephen Bantu Biko and said as ‘commoners’ they were

without a traditional mandate to lead the collective of black people.

The Accra Conference of liberation movement

leaders in Africa resolved to target 1963 for complete independence of the

entire continent. The PAC mobilised its supporters into an unfolding programme

of mass action until freedom is attained – by 1963. Critics oblivious of this

background information said Sobukwe’s target date was naive and unrealistic.

They claimed the masses were not ready for mass action.

For Sobukwe, the masses needed to assert their

African personality and overcome their fear of prison, then overcome their fear

of death, in order to overthrow white domination.

In the acclaimed autobiography, Long Walk to

Freedom, the author condescendingly remarks that Sobukwe was a clever man. He

then juxtaposes Sobukwe’s frustrations in handling difficult leadership merit

questions from an awkward personality at the Pretoria Central Prison when he

served three years for the consequences of the Positive Action Campaign. This

literary device is disingenuous and silly, because the parties treated with

disdain are not alive to corroborate the anecdotes or to tell their side of the

story. It is a cheap propaganda tactic.

HIS WIFE’S CONSUMING

LOVE

They met in the heat of a nurse’s strike in the

Eastern Cape and sparks of love ignited. When they became soul-mates in

matrimony, they also understood that their union was an everlasting bond. Ma

Sobukwe grew up partly in rural Kwa-Zulu and partly in the dark city of

Alexandra township. She has endured hardships – but was prepared beforehand for

the long road ahead of them. When she drafted the inscription on the gravestone

as a quote from his Completers Speech in 1949 she was transmitting the message

on true leadership as a consuming gift to the Azanian masses.

They met in the heat of a nurse’s strike in the

Eastern Cape and sparks of love ignited. When they became soul-mates in

matrimony, they also understood that their union was an everlasting bond. Ma

Sobukwe grew up partly in rural Kwa-Zulu and partly in the dark city of

Alexandra township. She has endured hardships – but was prepared beforehand for

the long road ahead of them. When she drafted the inscription on the gravestone

as a quote from his Completers Speech in 1949 she was transmitting the message

on true leadership as a consuming gift to the Azanian masses.

The writer is a

strategic management consultant. He is a member of the National Executive

Committee of SANMVA, the newly established statutory umbrella body of military

veteran’s organisations. He is the chairperson of the Pan Africanist Research

Institute (PARI).