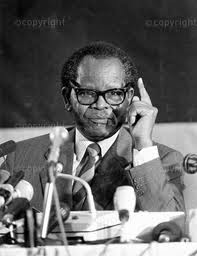

On 24 July 1951, Tambo qualified as an attorney. Mandela, by now also a qualified lawyer, had previously approached him to join in a partnership. They set up offices in Chancellor House, as Mandela and Tambo. As the firm became known, people travelled long distances, from around the country, to seek the services of the young law firm. When Mandela was banned in 1951, Tambo had to carry the workload on his own.

In 1953, Chief Albert Luthuli was elected President of the ANC and Tambo was appointed as National Secretary in place of Walter Sisulu, who had been banned by the government because of the Defiance Campaign. When the 1952 Defiance Campaign was called off, the ANC called a meeting of White activists. Tambo, Sisulu and Bram Fischer were the speakers at this meeting. Tambo carefully explained the aims of the Campaign and how Africans, Coloureds and Indians had responded to it. The audience was moved by his speech and shortly after this, the Congress of Democrats (COD) was formed, in 1953, with Fischer elected as chairperson.

When Canon Collins of St Pauls Church, London visited South Africa, in 1954, Father Huddleston and Tambo took him around to meet Sisulu and other ANC members. He spoke to Collins about his hopes of becoming an ordained minister of the church. This dream was not realised as Father Trevor Huddleston whom Tambo had come consider as his spiritual mentor was recalled to England in 1956.

At the 1954 ANC Congress, Tambo was elected Secretary General. That same year Tambo received his banning orders from the State. However, he remained actively involved in the background working as a member of the National Action Committee which drafted the Freedom Charter following extensive nationwide input and consultation. This was in the run up to the Congress of the People, (COP), convened in June 1955. When the COP was convened, Tambo could not attend due to the restrictions placed on him and had to observe the proceedings from a hiding place at Stanley Lollan’s residence in Kliptown, overlooking the square where the Congress was taking place.

During 1955 Tambo became engaged to Adelaide Tsukhudu, a nurse employed at Baragwanath Hospital. Their wedding was set for 22 December 1956, but it was nearly put off as Tambo was detained on treason charges on 5 December 1956. After all the accused were granted bail, the wedding took place as scheduled. After the preliminary hearings Tambo and Chief Albert Luthuli were acquitted. Altogether 155 members of the ANC were charged in what became known as the 1956 Treason Trial. In 1957, Duma Nokwe replaced Tambo as Secretary General of the ANC, while Tambo was elected Deputy President of the ANC. As early as April 1958 Tambo had confided in Adelaide that the ANC had wanted him together with the family to go into exile. By now the couple had three children, Thembi, Dali and Tselane.

During the ANC’s December 1958 conference the NEC appointed Tambo to chair the conference. A group of former ANC members, known as the Africanists, attempted to disrupt the meeting but Tambo was able to control the meeting leading them to eventually leave. The Africanists broke away from the ANC and in April 1959 constituted themselves as the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). More than a decade later, Tambo wrote a stinging criticism of the PAC, accusing them of being divisive and irresponsible.

In 1959, Tambo headed the ANC’s Constitutional Commission. The Tambo Commission recommended that more constitutional recognition be given to the ANC’S Women’s League (ANCWL) and the ANCYL, and endorsed non-racialism and the Freedom Charter, amongst other issues. The constitutional revision of the ANC came to be known as the Tambo Constitution. All the while he had to carry the burden of political work and the work of the law firm alone, since Mandela was still on trial.

In the meantime, Tambo began corresponding with a number of overseas sympathisers. Following the Sharpeville Massacre, Tambo embarked on a “Mission in Exile” in order to gain international support for the South African liberation movement. On 27 March 1960 Tambo was driven by Ronald Segal, the editor of the liberal journal, Africa South across the Bechuanaland (now Botswana) border. Whilst in Bechuanaland, telegrams that Tambo sent to the United Nations (UN) were intercepted and passed on to the South African authorities. Tambo’s stay in Bechuanaland became perilous and haunted by the constant fear of being abducted and returned to South Africa.

Yusuf Dadoo, the leader of the South African Communist Party (SACP) was also in Bechuanaland, having fled into exile. Frene Ginwala arranged travel documents and transport for Tambo, Dadoo and Segal from the Indian Consul in Kenya. The three men took off from Palapye, in a chartered plane to Tanganyika (now Tanzania). After spending a night in Nyasaland (Malawi), they landed in Dar es Salaam, Tanganiyika where they were met by Ginwala who took them to meet Julius Nyerere.

After that Tambo flew from Tanganyika to Nairobi, where he was issued with further travel documents by the Indian Government. The next day Tambo left for Tunisia where he was invited by the General Secretary of the World Assembly Youth, David Wirmark. It was here that he delivered his first speech outside the country. He also met President Habib Bourgiba of Tunis and was able to explain the ANC’s position to him. From here, he went to Ghana where he had an audience with Kwame Nkrumah and explained the situation in South Africa.

Tambo’s first visit to northern Europe was when he went to Denmark at the invitation of the Prime Minister on 1 May 1960. He addressed meetings in Copenhagen and Aarhus outlining the history of South Africa and called for trade unions to help the ANC’s boycott call. From here, he flew to London where he was met by his friends Father Huddleston and Canon Collins. In London, he had meetings with ANC exiles, Dadoo and representatives of the PAC. His intention was to try to bring together representatives of the liberation movements fighting the South African regime.

Thereafter, he flew to Egypt to enlist the support of the Egyptian leader, Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser. From here he flew to Ethiopia where he met with the Non-European United Front, a body made up of ANC and PAC exiles, that was set up to work together with a common purpose. Whilst in Ethiopia, he also addressed the first conference of African heads of state.

At the same time, arrangements were made for Adelaide and the children to travel to Swaziland and from there to Ghana and then on to London. A farmer from Swaziland, Oliver Tedley, transported them across the border into Swaziland. After six frustrating weeks, Adelaide and the children left for Botswana and from here, landed in Accra, Ghana three weeks later. A week later, on 15 September 1960, Adelaide and the children landed in London. Initially they stayed with James Philips a South African exile.

In the meantime Tambo had to go to New York to address the UN. The family then moved into a flat and Adelaide was able to find a job as a nurse at St George’s Hospital. There were times when she had to leave the children alone, locked up for the night, to work the night shift. In the years to come, Tambo saw very little of his family due to his hectic travelling and ANC commitments. Adelaide was forced to work between 12 and 20 hours per day to earn enough for the upkeep of the family. In addition, Adelaide opened her house to members of the ANC arriving in the United Kingdom. Tambo had little money and hardly spent his ANC allowance of £2 a week on himself, saving whatever he could for Christmas gifts and cards for his children.

In October 1962, a consultative meeting chaired by Govan Mbeki, was held in Lobatse, Botswana. It was to confirm the ANC’s NEC mandate, namely, that Tambo was to head the ANC’s diplomatic mission and to communicate to the world the situation in South Africa. As head of the ANC’s Mission in Exile, he had to oversee the growing number of ANC exiles, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) military camps, fundraising, the setting up ANC offices around the world, the welfare of ANC cadres were well taken care of and to interact with the international community. His use of consensus and the collective decision making helped tremendously.

When Chief Luthuli was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1961, Tambo accompanied Luthuli and his wife throughout their travels to Oslo. In January 1962 Tambo met Mandela and Joe Matthews in Dar es Salaam. Mandela explained to him the details of the decision to launch MK and armed operations, and the ANC’s need to cooperate closely with the SACP in this process. Mandela and Tambo then worked out a programme for the External Mission under the new circumstances whereby the latter had to develop diplomatic support for MK.

Mandela and Tambo travelled to a number of countries in North Africa. Together they returned to London where Mandela met with a number of important British officials and politicians. During this period Tambo also led an ANC delegation to the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in Ethiopia in May 1963. In July 1963, the bulk of the MK High Command were arrested. With the incarceration of the Rivonia trialists, it fell upon Tambo to take up leadership of MK.

In 1963, he visited the USSR and China, hoping to gain support from these two countries. The USSR made £ 300,000.00 available to Tambo in 1964. He was later to say that it did not mean that since the ANC was accepting assistance from the USSR that it was aligned to the Russians. At the same time, he had worked to win over Western countries in order to gain support from them. In 1964, Tambo arrived in Dar es Salaam to take up his post as head of MK and the ANC. He shared a guesthouse with other members of the ANC office.

During 1963 and 1964, Tambo made a number of high profile speeches to present the ANC to the world, the most prominent being one made to the UN in October 1963. This speech inspired the UN Resolution XVIII of 11 October 1963 calling on the South African Government to release all political prisoners. Tambo addressed the UN where his passionate plea for the release of political prisoners received a standing ovation. It was at the UN that Tambo met ES Reddy, an Indian national who was the Secretary of the Special Committee on Apartheid. The two men developed a long lasting, enduring friendship. Over the years Reddy became a useful ally of Tambo and the ANC. Support for the ANC’s cause abroad also came from the London Anti-Apartheid Movement. In 1964, Ronald Segal together with the London Anti-Apartheid Movement and Tambo’s involvement organised an International Conference on Economic Sanctions against South Africa.

Following the Rivonia Trial, Tambo called a consultative meeting of ANC representatives from around the world, in Lusaka on 8 January 1965 as it was becoming difficult to meet with the increasing number of branches being set up internationally. That same year he also negotiated with the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now African Union [AU]) and the Tanzanian Government for land to set up a military camp in Dar es Salaam. In 1965, he also set up another camp in newly independent Zambia.

At the same time, MK and Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) began to work together with the aim of infiltrating then Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). In 1968, Tambo accompanied the MK group on a number of occasions when they went on reconnaissance expeditions along the Zambesi River, sleeping in the open with the group. Tambo named the group the Luthuli Detachment, in honour of Chief Luthuli who was killed in a tragic railway accident in July 1967 in Groutville, Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal). The Wankie Campaign was the first significant military campaign for the ANC. In spite of some victories against Rhodesian forces, the group was forced to retreat, as they had to face the military might of the combined South African and Rhodesian forces.

OR lived under constant pressure and stress, which at times affected his health and given the demands of his position he had little time to recuperate from illness. At the same time, there were strident criticisms from rank and file members over a host of issues ranging from military to social to political.

A memorandum from Chris Hani’s group that was incarcerated in Botswana following the

Wankie Campaign issued a scathing memorandum, upon their release, of various senior ANC leaders and accused Tambo of failing to adhere to democratic principles. Tambo was disturbed by the memorandum and at the low morale in the camps. As a result, he decided to call a consultative conference of the ANC. He sent word, secretly, to the leadership on Robben Island about the conference. After months of intense preparation, the conference of about 700 ANC members in exile, MK and the Congress Alliance partners took place on April 1969 at Morogoro, Tanzania. In his address to the conference, Tambo emphasised that it was a consultative conference.

At this meeting, Tambo tended his resignation from the ANC, following personal attacks. This threw the conference into disarray and Tambo was persuaded to return. A new executive was elected and Tambo was unanimously re-elected as President. This position was endorsed by the leadership on Robben Island in a message conveyed by Mac Maharaj following his release from the Island. The leadership was restructured into the Revolutionary Council, chaired by Tambo and included Yusuf Dadoo, Reg September and Joe Slovo. Tambo kept updated about discussions on the Island as he was briefed by prisoners who were released and through correspondence, via various sources that he had clandestinely developed, was able to communicate to the leadership on the Island.

In the aftermath of the 1976 student rebellion, Tambo had to rethink ways of effectively managing the organisation. He approached the Tanzanian Government for a piece of land to establish a school for exiles. The school was named after Solomon Mahlangu, an MK guerrilla who was executed by the Government after an attack on a warehouse on Goch Street, Johannesburg. He also recruited Pallo Jordan to develop Radio Freedom, on which Tambo often spoke, in Lusaka to broadcast ANC propaganda.

Tambo reached other organisations such as the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). However, the death of Steve Biko at the hands of the police in detention and the banning of other BCM activists meant that a planned meeting with the BCM leaders was set back. Tambo also met a number of visiting homeland leaders, in particular, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) in London. In 1978, Tambo headed a delegation to Vietnam where they attended numerous lectures and met with activists in the Vietnamese struggles. Subsequent to this visit, he commissioned a Politico-Military Strategy Council to lay the groundwork for mass support and mass mobilisation. The Commission recommended a programme whereby all opposition groups within the country would join forces around a broad programme of opposition to Apartheid.

Tambo was very mindful of the rights of women. He commissioned a Code of Conduct that saw that women’s rights are respected and upheld by all in the organisation. He tried to ensure that the abuse of women was eradicated.

Between 1983 and 1985, there were two mutinies in MK camps in Angola. Young cadres who wanted to be deployed back home mutinied when this did not take place. In addition deteriorating conditions at the camps also contributed to the mutiny. Tambo appointed James Stuart to head this Commission to investigate. It became known as the Stuart Commission. However, as early as 1983, Tambo visited camps, in Angola, to address cadres based there. Whenever he visited the camps, he would talk to the cadres about their problems. At times, he even entertained what one may consider trivial personal issues.

Following the signing of the Nkomati Accord between South Africa and Mozambique, cadres in the camps mutinied again, demanding to return home to fight. Again, Tambo addressed the cadres explaining to them the need for diplomacy under the circumstances, with the need to balance the undertaking of the armed struggle back home. As a result of growing frustrations of cadres in camps, in 1985, another ANC consultative conference took place in Kabwe, Zambia. Amongst many important issues that were dealt with and decisions that were arrived at, Tambo commissioned a Code of Conduct to deal with issues of procedure and detention. However despite the Code of Conduct, abuse in the camps did not stop.

Tambo remained acutely aware of the need to make and keep contact with both the civil and the corporate world. Already by the 1980s, he had met with American multinationals in order to explain the ANC’s position to them. Whilst Tambo was expanding the ANC’s network on a diplomatic, corporate, cultural and sporting level, the South African regime was becoming increasingly even more repressive at home and was engaging in more cross border raids.

On 8 January 1985, Tambo delivered his most dramatic speech calling on people to “Render South Africa Ungovernable.” Following the July 1985 State of Emergency, he appealed to all South Africans, Black and White, to make Apartheid unworkable and the country ungovernable. With social unrest increasing and the Apartheid Government under pressure, Tambo stated that this alone was insufficient and that alternative people’s structures had to be built.

That same year Tambo and the ANC met a high-powered delegation of the foremost captains of industry from South Africa. This meeting was due to the efforts of Gavin Relly, a director at Anglo American. At this meeting Tambo explained the ANC’s position and fielded questions from the understandably apprehensive business people. Subsequent to this meeting, the National African Confederation of Commerce, a Black business grouping, headed by Sam Motsunyana, also met with the ANC.

In October 1985, Tambo was asked to give evidence to the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Commons in London, where he had to field difficult questions and sometimes hostile questioners. The result of this was that the following year, the United Kingdom, as part of the Commonwealth, sent an Eminent Persons Group to investigate the situation in the country. Then in 1986, he called for a campaign to establish an alternative system of education and called for the unbanning of the Congress of South African Students (COSAS).

In 1987, Tambo appointed a high-powered Commission of ANC legal people to draw up a constitution to reflect the kind of country that the ANC wanted for the future. He also sat in on these meetings, often guiding the meetings. Tambo had consistently advocated support for a multiparty democracy and an entrenched Bill of Rights. Also in 1987, Tambo together with others conceived and headed a top-secret covert mission by MK known as Operation Vula. Tambo chose the operatives to infiltrate into the country to work underground establishing networks and arms caches.

In 1988, Tambo called an emergency meeting of the ANC’s Politico-Military Council (PMC) to determine the position of MK operations in South Africa. In spite of the South African Defence Force (SADF) massacring ANC members in Lesotho, Botswana and Mozambique, Tambo insisted that the ANC should maintain moral high ground and avoid the loss of civilian life in its operations. This was in response, especially, to when MK struck at two “soft targets,” fast food outlets in the country.

In 1988 Tambo appointed a President’s Team on Negotiations to draw up the ANC’s position and approach to the negotiations drawing from viewpoints from the exiles and the Mass Democratic Movement in the country. In the meantime, the South African establishment was secretly making moves to approach the ANC for negotiations through exploratory meetings. On 31 May 1989, Thabo Mbeki, after receiving the go ahead from Tambo called Professor Willie Esterhuyse, who had been part of these meetings, to set up a meeting between the ANC and the South African National Intelligence Service. Mbeki was in many ways a protégé of Tambo as the pair worked very closely together.

Following extensive discussions with the Front Line State leaders, Tambo led and worked closely with the ANC team which drafted the Harare Declaration. The declaration acknowledged that there may be an opportunity for negotiations with the South African regime with the end of Apartheid in mind. It explained the climate and principles, which had to be created, before negotiations could begin.

Pressure and exhaustion took its toll on Tambo and in 1989 he suffered a severe stroke that resulted in him losing his speech. Following his stroke, he was rushed from Lusaka to London on Tony Rowland’s executive plane on the order of President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, to Harley Street in London. Rowland also paid for the medical treatment. Against the advice of his physician and the NEC, Tambo continued his punishing work schedule and travelling on ANC business. He suffered another stroke in 1991 whilst undergoing medical treatment in Sweden. Again Rowland flew him back to London where he was treated.

With the unbanning of the ANC in 1990 and the process of transition already underway, the entire Tambo family flew back to South Africa in December 1990. However, Tambo was unable to address the welcoming crowd at the airport due to his loss of speech. A welcome rally was organised at Orlando Stadium, attended by a crowd of 70,000 people. At the ANC Conference, in Durban in 1991, Tambo declined to stand for any position. The position of National Chairman was created in his honour. Nelson Mandela was elected President of the organisation.

In 1991, Tambo was installed as Chancellor of the University of Fort Hare. In February 1993, he opened a large international conference in Johannesburg, chaired by Thabo Mbeki. Foreign dignitaries and representatives of anti-Apartheid movements filled the hall to listen to Tambo thank their countries and organisations for their contribution in helping to end Apartheid. Despite his illness, Tambo came to the ANC, in Johannesburg, office every day and still addressed public meetings of organisations.

During the early hours of the morning of 23 April 1993, Oliver Reginald Tambo passed away after a heart attack. He was honoured with a state funeral where scores of friends, supporters, colleagues and heads of state bade him farewell. His epitaph, reads, in his own words:

It is our responsibility to break down barriers of division and create a country where there will be neither Whites nor Blacks, just South Africans, free and united in diversity.

Position:

President (1967 - 1991) Deputy President (1958 - 1985) General Secretary (1955 - 1958)

References

• Callinicos L. (2004), Oliver Tambo. Beyond the Engeli Mountains, (David Philips Publishers), Claremont, Cape Town

• Jordan, P.Z. (2007). Oliver Tambo Remebered. Pan Macmillan, Johannesburg

• ANC (date unknown).Oliver Reginald Tambo. Available at www.anc.org.za online. Accessed on 17 October 2011

Biography retrieved from the South African History Online at

http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/oliver-reginald-tambo

On 24 July 1951, Tambo qualified as an attorney. Mandela, by now also a qualified lawyer, had previously approached him to join in a partner...